Leaving Orsha

My grandmother Celia (Zipa) Merkin, and five of her six living children immigrated to the United States in the early years of the 20th Century. The family came from Orsha, a small town at the confluence of the Dnieper and Arshytsa rivers, about 200 kilometers from Minsk. Orsha was a part of Tzarist Russia then.

My mother, Katia, remembers Orsha as a dismal place – flat and poor and ugly – cold and snowbound for long winter months, hot in the summer, and muddy most of the rest of the year. The single fond memory she carried of her home village was being allowed to run free one spring through an enormous field of blue cornflowers.

My Grandfather Yehudah, was a Talmudic scholar. My Grandmother Zipa (Celia) was a baker, and the main support of the family. Six Merkin children – one boy and five girls – survived to adulthood. The oldest surviving children were Rebecca and Sam (Shmuel). There was a gap after the two were born —several infants came along but did not survive. Then came four daughters, born early in the 20th century. All survived. Katia (Kusia) was the first child in this almost-second family to live beyond childhood. Then three more girls were born: Ida (Chaje), Miriam (Maryosh) and Anita (Chaska).

Not long after Anita’s birth in about 1904, Yehudah Merkin died. Then, in 1905, there was a pogrom in Orsha — carried out while Russian authorities did nothing. Thirty Jewish residents of Orsha were killed. My mother and Ida both remembered that pogrom — they watched it, terrified, from the root cellar of their Orsha home.

It was time for the family to leave

Coming to America

Sam was the first of the Merkins to come to the United States. He arrived in 1909 — it had taken four years for the family to save money for his steerage class passage.

It took another three years for Sam, in America, and his mother, in Orsha to save enough for the next Merkins to travel to New York. Ida and my mother came in 1912. The two girls — Katia and Ida — immediately took jobs as seamstresses and, along with Sam, began saving money to pay the fare for their mother and their two youngest sisters to come to America.

By 1913, Sam, Katia and Ida, together, managed to save enough money to pay passage for my grandmother Zipa and the two youngest girls.

Rebecca was the only sibling to remain in Orsha — by 1912 she had married and settled into her own life away from siblings.

After the arrival of Zipa and the two youngest girls, the whole family, except Rebecca, lived together in a small tenement apartment on Broom Street in New York’s lower east side.

But gradually, as they became more solvent, grew, married, and moved out, Ida, the last daughter left at home, took on the responsibility of caring for her mother. This was a typical fact of immigrant life and probably of life for those who remained in the stetls of Eastern Europe as well: my father’s sister Helena, took on the same responsibility for my Halborn grandmother, Nisla Mirla Freulich, after he and four of his siblings moved on. She continued with this responsibility until my grandmother died, in the Łódź ghetto in 1940.

How Old Were They?

No one in the Merkin family knew exactly how old they were when they left Orsha. Sam, according to the ship manifest for the Roon, which docked at Ellis Island in December, 1909, was 22 years old. Katia and Ida are listed on the manifest for the Nieuw Amsterdam, which carried them to New York in December 1912, as 19 and 17. Their passport, issued just two months before they traveled, lists them as 17 and 14. When the two youngest girls arrived a year and a half later, in July, 1913, Zipa's age is listed as 48, Miriam's as 11, and Anita's as 8.

Belarus has been slow to provide whatever skimpy records might still exist that might have additional information about their birth years. And official documents in the United States only add to the confusion for the entire family: Zipa's birth year appears in various documents as 1860,1865 and 1882. Sam’s as 1902, 1890,1887,1889 1882. Katia’s as 1900, 1898, 1902, 1896. Ida’s as 1901, 1898. Miriam’s as 1904, 1903,1902. And Anita’s as 1904, 1906, 1901,1905.

It is likely, given both the years in which they died the three working members of the family were younger than immigration records indicate. Sam was probably about 19 when he came to America in 1909, Katia was about 13, and Ida about 12.

Anecdotal information seems to confirm that Katia and Ida were much younger than the ages listed on the ship manifest. Both sisters consistently told me that their mother worried about their traveling alone, without an adult, and worried about their ability to find employment in the United States. So having no exact record of their birth, Zipa stated that they were 19 and 14 when she obtained their passports, and then made sure that the older sister, Katia, traveled on an adult ticket. And both Ida and Katia told me that when they left Europe their mother provided them with prim and adult looking clothing to wear when they presented themselves to immigration authorities.

Labor Laws

The use of children in factories in the United States at the turn of the century sheds additional light on the situation for Katia and Ida. By 1900, several state legislatures began passing laws forbidding the employment of children under 14 or 15 years of age in full time work. New York was one of those states, especially after the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire killed 150 workers in the New York garment district just a year before Katia and Ida were seeking employment in the garment industry.

Despite the debate, Katia and Ida, were desperate for work. They knew that their task was to help Sam provide enough money to bring their mother and two youngest sisters to the United States as quickly as possible. They probably dressed in the severe clothing their mother had provided. And they were able to obtain full time employment in a shirtwaist factory within weeks of their arrival in New York.

So, were they really old enough to work full time — something that involved 10 and 12 hour days in the early 20th Century? Or was their employer violating state law or, at the least, violating the spirit of the laws that were then being hotly debated within New York City?

Once again, anecdotal information provides a clue. Both my mother and Ida told me that, after a short time at their jobs, the shirtwaist factory owner took them aside and told them he knew they had lied about their ages. They were violating the law, he said, and they were putting his business in jeopardy. So, if he wanted to keep his business open he would have to report them to authorities unless they agreed immediately to work for half pay. He might lose his factory. They would certainly lose their jobs and would probably be deported.

Whether or not there were actual law on the books at that time is besides the point. Either way, Katia and Ida were not violating any law. If anyone was, it was their employer. Child labor laws, when they were passed, were intended to protect children and punish employers who exploited them.

But, of course, Katia and Ida were ignorant of American law, and they were frightened. So they quickly agreed to continue working full time and to accept half the pay other seamstresses were earning. And, of course, their acquiescence protected their employer — he could simply display his payroll account to anyone intent on enforcing child labor laws. Rather than showing that he was exploiting two children, the payroll would prove that these two children were earning only half time salaries, so obviously they were only working half time.

New York and Los Angeles

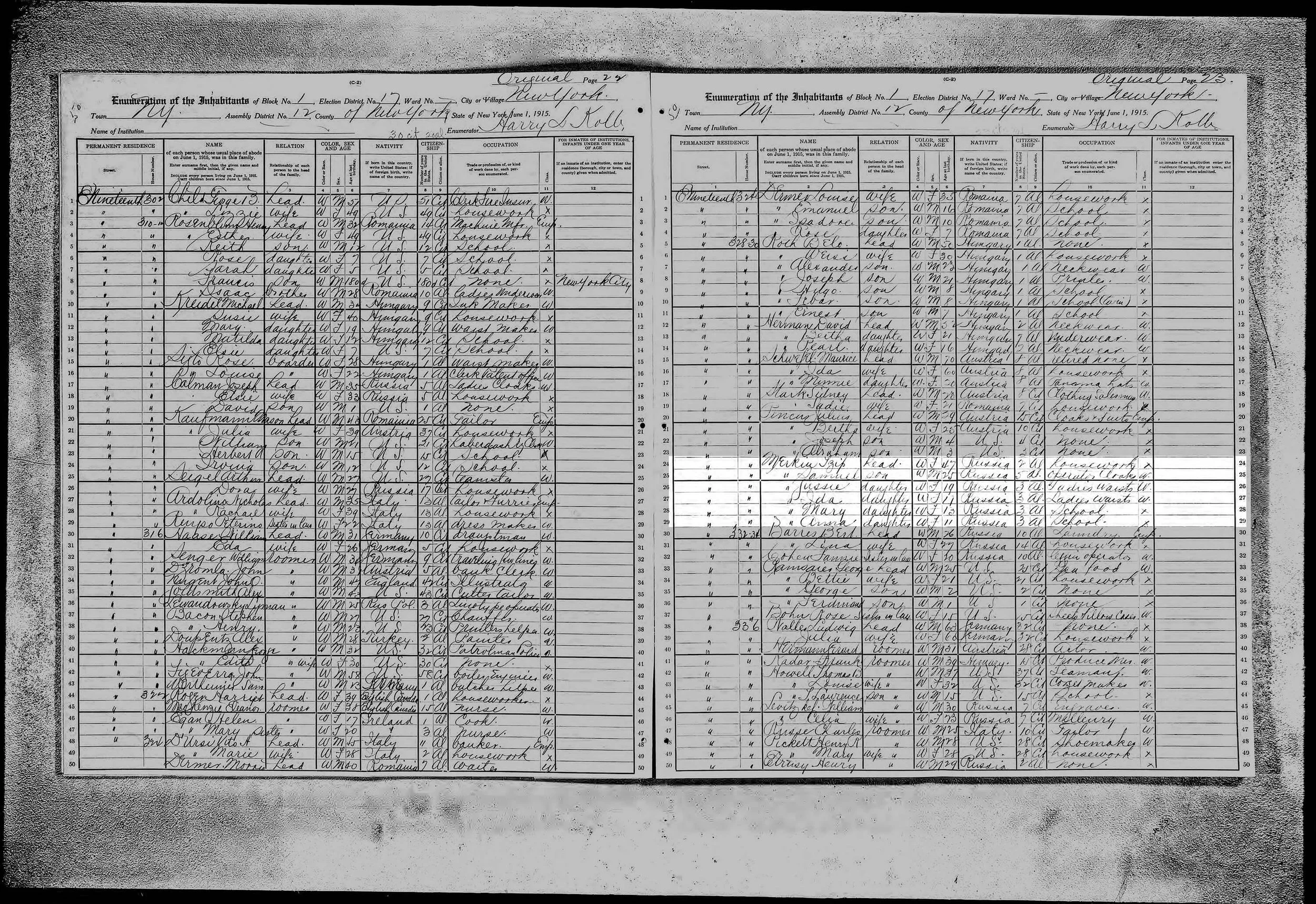

In the 1915 New York State census, all five of the Merkins who came to America — “Tzip” (Zipa), Samuel, “Gussie” (Katia), “Mary” (Miriam), and “Anna” (Anita) are listed living together at 328 19th Street in the Lower East Side of New York. Zipa is listed as the head of the family, 47 years old; Sam is listed as a 25 year old cloakmaker; Katia is 19 years old; Ida 17. Both are still working in “Ladies Waists”. Miriam, age 13, and Anita, 11 years old, are attending school.

By the time of the 1920 national census, Sam had his own apartment, had become a cloak manufacturer, married Ray Michanovsky, another immigrant, and the couple had an infant son, my cousin Irving (Bill) Merkin, the first of three sons of Sam and Ray. The four sisters continued to live with their mother and remained close to Sam and his growing family.

By the time of the 1930 census, there were more changes: In 1924 my mother married Halborn descendant Roman Freulich, and left the East Coast for a new life in Los Angeles. At about the same time, Ida became engaged to Abraham Riskin. And one year later, their younger sister, Miriam, married Louis Bernstein. The Bernstein's daughter, my cousin Eunice, was born in 1927 and five years later, the family moved to Los Angeles.

My mother, Katia Merkin, worked in the New York garment industry for twelve years before she married and began a new life with my father. Her younger sisters, Miriam and Anita, were spared that fate and were able to attend school. Probably both completed high school. Miriam went on to complete several years of college.

Ida continued working in the garment industry and became active in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. She worked from 1912 until the mid 1960s. And even after retirement she continued to volunteer with the ILGWU, counseling new refugees — who by that time were mostly people from Hispanic and Asian lands — in preserving their rights as garment workers.

Miriam and Ida remained my favorite Aunties and remained close to one another for the rest of their lives, though Miriam and Katia lived in Los Angeles and Ida continued to live in New York.

What I know about Ida and her husband, Abraham Riskin, is the subject of two other stories — Second Avenue Deli and The Sibling Keeper.