Alytus to the Internet, part 2

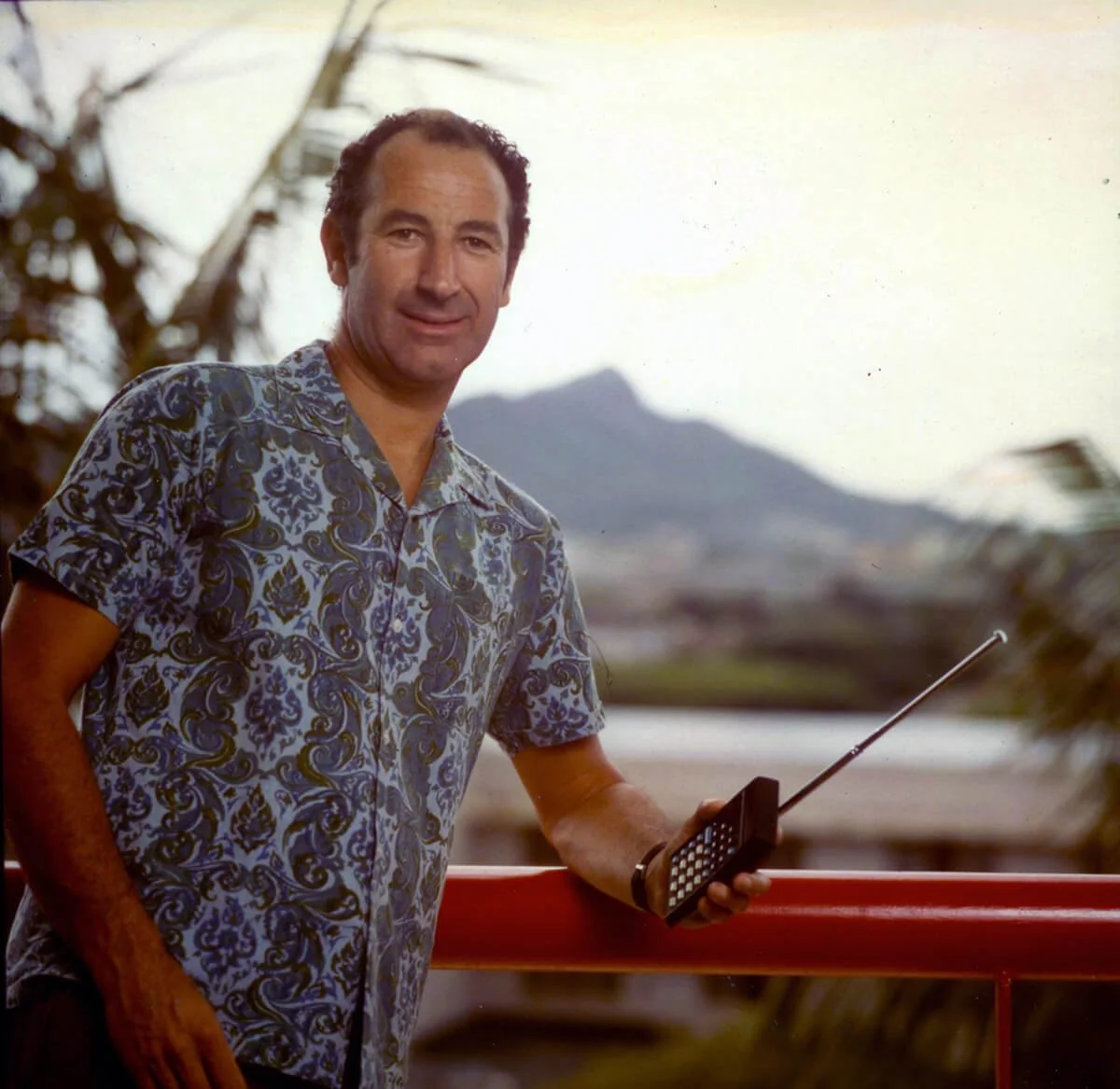

Norman Abramson surfing Waikiki, 1989.

Ellis Island

So, what does the name Matskevitch have to do with the name Abramson? The answer begins with Shimsel Matskevitch, Norm's uncle and one of the two first Matskevitch siblings to arrive in the United States.

Shimsel and Minna Matskevitch arrived at Ellis Island in August 1907 aboard the steamship Patricia along with Shimsel's new wife, Rachel Braverman. Shimsel and Rachel, who was also from Alytus, had apparently married earlier that year. The destination of all three is listed on the ship manifest as Reading, Pennsylvania, where Shimsel had a job waiting for him as a teacher in a Hebrew school.

A frequently repeated family story says that Shimsel was confronted at Ellis Island by a baffled immigration officer who sent him to a phone booth to consult the directory and pick a new name. Shimsel, anxious to begin his new life, went to the first page of the directory and picked the first name he saw.

We do not know (and we doubt) that directories or public phone booths were available at Ellis Island in 1907. And in our Halborn family book we noted that stories of names changed at Ellis Island, while they exist in many families with immigrant ancestors, are variations on a myth. No such name changes were possible. Immigration officers did not create lists of the people passing through. They used ship manifest that had been created by a ship's officer as passengers began their journey as the basis for their questions. They went through the information and checked off each incoming passenger. Hopeful immigrants were either admitted, held temporarily for health or other reasons or rejected.

But Shimsel did change his name sometime soon after he arrived in the United States.

While the name Matskevitch was probably acceptable in his new workplace, which was Jewish and likely full of men from Alytus or nearby Lithuanian towns, it was not a name that could easily be pronounced or spelled in the wider world of America, or even in Reading, Pennsylvania.

Shimsel took the logical step – indeed, the biblical step – of adopting the name Abramson. He was, after all, the oldest son of Abram Matskevitch. He also took the first name Samuel, which could at least be spelled accurately by most of the Americans he encountered in his daily life. The three younger brothers who followed him to America simply followed his example. In Alytus they were Matskevitch siblings. The ship manifests for all of them list them as Matskevitches -- Yrmil, Osher and Motl. In America, after they settled, they became Abramson siblings -- Harry, Edward and Max.

For Minna, the problem of having a difficult name was not as urgent. She probably began her stay in the United States in Reading, living with her brother and sister-in-law and did not bother to formally change her name. But in 1915, in Boston, she married a widower named Joseph Smalowitz. It is even possible that by 1915 she, too, was widowed and had given up the name Matskevitch well before her Boston marriage. We know the Boston marriage registry lists her with two last names, Matskevitch and Bernstein.

Reading, Pennsylvania

Samuel Abramson lived and taught in Reading. He and his wife Rachel had seven children, six of whom lived to adulthood. As the oldest sibling in America, Samuel took on the role of head of the family. His home in Reading was often the first stop for the Abramson siblings when they came to America. Yirml – Harry Abramson – was next to arrive. He passed through Ellis Island in 1911. Osher – Edward Abramson – arrived in 1922, and Motl – Max Abramson – arrived in 1927. Later, when it was time to introduce intended wives or growing children to Samuel and his family there were other visits to Reading.

Samuel continued to live in Reading for the rest of his life. But the four younger siblings who came to America all settled in the Jewish neighborhood of Dorchester, in Boston, Massachusetts. Visits were rare – Boston is, today, a five hour car journey from Western Pennsylvania. In the 1930s, it was probably at least a 10 hour drive. All five of the siblings who had immigrated were photographed together at least once, probably in the early 1930s.

Eddie, the youngest of the siblings to immigrate, bought a car sometime in the late 1930s. And Norm, who was born in 1932 remembers annual summer visits he made to his Reading family as a young boy. He recalls standing in the back of the family's sedan, holding on to the braided rope hand-hold that stretched across the back of the front seat and looking out at the passing scenery, fascinated by the entire journey. He often says those trips were the beginning of his interest in travel.

Dorchester, Massachusetts

The Dorchester neighborhood where Harry, Mamie, Eddie and Max married, lived and raised their families and where Norm grew up was a small section of southwest Boston – the Jewish section in the 1930s and 1940s.

In Dorchester Eddie met another immigrant, Esther Vaslavsky. Esther had come to America from Odessa with her sister, Bertha. They arrived at Ellis Island in January, 1923, and were living in Dorchester at the home of their older sister, Sophie, her husband, Fred, and their two children. In 1929 Eddie and Esther married.

We do not have photographs of all the family members of the Abramson siblings who lived Dorchester. But there were many. Minna, the oldest of the four was stepmother to two children and birth mother to two more. Harry and his wife had three children, Max and his wife had two, and Norm's father and mother had two. In that small neighborhood, all within a short walk of one another, there were 11 Abramson cousins, born between the early 1920s and 1942. On his mother's side, living in the same small neighborhood, there were an additional four cousins, born between 1914 and 1936.

Norm describes Dorchester, where he spent the first 17 years his life, as a transplanted shtetl -- a bit of small town Eastern European Jewish life transferred, almost intact, to the middle of a major city in the new world. Social life in Dorchester in the 1930s and 1940s centered around extended families and on synagogues and shuls, men's and women's groups that supported various Jewish causes and were at the heart of most social events, and landsman clubs organized according to the old world towns and villages where people in the neighborhood had been born. Norm's father, Eddie Abramson, and his uncles, were member of the Alytus Landsman organization -- the Alytus Relief Society..

For Norm, who was born in 1932, Dorchester was a place where he was surrounded by family. Three of his father's siblings and their families lived within walking distance for most of his childhood, as did two of his mothers siblings and their families. Some lived on the same block of the same street. There was always a place to go when his parents were out. There were always cousins to play with. There was always someone watching and willing to report any perceived mis-behavior on the part of any of the family's many children. And there was always a guarantee that any family event would be crowded with relatives.

Norm's memories, along with those of some of his cousins, often seem to center on what might be called mis-behavior -- or, if one chooses to put a positive spin on it, intense curiosity. He remembers attaching CO2 cartridges to model cars to see how far he could propel them down the long hallway that went between the front and back of the downstairs apartment in a two family home where his family lived -- and leaving permanent marks on the paint at the end of the hall when he launched a particularly successful model car run. He remembers a huge blackened area he left on the kitchen ceiling, much to the consternation of his mother, when he mixed and heated chemicals from the chemistry set he was given as a gift. He remembers playing poker with friends when he was supposed to be baby sitting his younger sister and using a younger cousin as "lookout" to warn the group to flee when his parents could be seen approaching home. He remembers playing hooky from Hebrew school after his bar mitzvah. He had by then completed six years of classes five days a week after public school but he was expected to continue taking Hebrew school classes for another five years, until he graduated high school. He remembers exploring beyond the borders of his Jewish neighborhood, motivated by trying to avoid the small ultra-orthodox shut that stood next to the family's home -- the few remaining old men who used the shul, if they spotted him, always insisted he join them to make up the minyan of ten men required before they could hold a prayer service. He remembers constant disciplinary problems at Boston Boys' Latin High School -- the public school reserved for Boston's brightest students. He was expelled from Boys' Latin for bad behavior after tenth grade and instead graduated, first in his class, from Boston's second best public school for boys -- Boston Boys' English High School.

Leaving the Shtetl

Despite what may have once been perceived by some as "bad behavior" – or perhaps because that behavior was perceived by college admissions officers as "intense curiosity" – Norm had no problem being admitted to Harvard. And Harvard opened up a wide range of experience and learning – everything from English pronunciation he had never heard in Dorchester to a world that could be explored through psychology, history and, especially, through science and math.

Harvard was the beginning. Norm graduated in 1953 with a major in physics. Harvard was followed by a Master's degree in physics at the University of California, Los Angeles – a destination that provided him with a full scholarship and a chance to travel across America. Next came a teaching assistantship and a PhD in Electrical Engineering at Stanford and a position as Assistant and then Associate Professor at Stanford.

Norm did not leave the academic world again until his retirement, in 1994. And even then he continued to create, write, and lecture all over the world.

Hawaii to the Internet

In 1965, traveling back from a lecture he gave in Tokyo, Norm stopped for a few days on Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands. The warmth and the surf intrigued him. So did his discussions with some very bright people who had been brought in to help improve the Electrical Engineering Department at the University of Hawaii, and who offered him a job.

I don't doubt that two factors were equally balanced in Norm's mind. The Islands and the surf spoke for themselves. And the University, though not of the same rank as Harvard or Stanford, offered some exciting possibilities. It was relatively new to research, it was, at the time, well managed and well supported by the State of Hawaii, and it offered the opportunity to shape some exciting new programs and to invite major researchers from the United States Mainland.

By the time he was completing his masters at UCLA in 1954, Norm and I had married. By 1965, when he returned from his Asian trip, we had two small children and a new home in the hills behind the Stanford campus. But we decided to leave Stanford behind and move to Hawaii.

It was a decision that led to the technology that, to this day, is used in all two way wireless communication devices -- in cell phones, tablets and wireless computers and even those little devices that allow restaurants to run credit card charges through at your table. It allows us to phone and text and search the internet wirelessly wherever there is a wifi signal available.

It is a technology that is called, appropriately, ALOHA (and SPREAD ALOHA, with the additional research Norm did in more recent years). No one today remembers what the acronym ALOHA stands for. But the technology has been the subject of thousands of PHD theses, research papers, books and patents. The technology, he said, would one day enable wireless phone, text and computer communication.

A photo of Norman Abramson taken in the mid-1970s, before the personal computer (1980) and the cellular telephone (1983). The photo was taken while he led the ALOHA Systems laboratory, the group which developed the ALOHAnet, which implemented the first wireless data network. He is holding a mock up of a wireless communication device he predicted would be enabled by the new digital technology. The mock up was put together with a small digital calculator and an automobile antenna.

Sitting on a surfboard in the warm waters off Waikiki, looking out over the vast Pacific ocean while waiting for the next set of waves to role in certainly had a part in Norm's thinking. The problem was there, for him and for Hawaii: communications between Hawaii and the Mainland of the United States, communications between Hawaii and Japan, and even communications between the eight Hawaiian Islands was expensive, slow and unreliable.

Norm's research at the University of Hawaii was partially funded by the National Science Foundation, partially by the Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Administration, and pally from private industry grants from IBM and Nippon Electric. With that funding the ALOHA Systems laboratory at the University of Hawaii, under Norm's direction, first began testing wireless random access protocols on the ground. The first link was a wireless connection that traversed a few blocks between the ALOHA System laboratory at one side of the University of Hawaii Campus and New College, where I worked, at the other side. The next went a mile, between the University, at the entrance to Manoa Valley and our home. Next, the project connected University of Hawaii campuses on the outer islands -- primarily Hawaii and Maui. All of these links were provided by an ALOHA channel.

The ALOHA network was connected to the Internet (then called the ARPAnet) in 1972. Norm described the almost accidental timing years later in an article in the IEEE Communications Magazine:

Sometime in 1972, I was visiting Roberts' office in Washington for discussions dealing with both technical and administrative matters in the Aloha System when he was called out of his office for a few minutes to handle a minor emergency. 1972 was a year of rapid growth for the ARPANet as the Interface Message Processors (IMPs) that defined the nodes of the network were installed in the first network locations. While waiting for Roberts to return, I noticed on the blackboard in his office a list of locations where ARPA was planning to install IMPS during the next six-month period, together with the installation dates. Since I planned to bring up the question of installation of an IMP at the Aloha System laboratory in Hawaii to be used with the satellite channel discussed above, I took the chalk and inserted "the Aloha System" in his list and beside it placed the date of December 17 (chosen more or less at random). After Roberts' return, we continued our discussion but because of at the rather long agenda, we did not discuss the installation of an IMP in Hawaii, and I forgot I had inserted an installation date of December 17 for us in the ARPA schedule on his blackboard. I never did get the opportunity to discuss the installation of an IMP in our laboratory with Roberts. Instead, about two weeks before the December 17 date, we received a phone call from the group charged with the responsibility of installing the IMPs asking us to prepare a place for the equipment. On December 17, 1972, an IMP connecting the ALOHA system and ALOHANet to the ARPANet by means of the first satellite channel in the ARPANet was delivered and installed.

The ALOHA project then implemented the next step, PacNet, in 1973. PacNet became the first satellite network to utilize random access packet transmission in multiple links. The experimental network used the ATS-1 satellite and wirelessly linked the University of Hawaii to the NASA Ames Research Center in California, the University of Alaska, Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan, the University of Electro-communications in Tokyo, the Korean Institute of Science and Technology and the University of Sydney in Australia.

Within a year of the first ALOHA link in Hawaii, ALOHA technology was adopted to cables by XEROX and initially called the ALTO ALOHA Network and then called Ethernet.

Norm’s Awards

Like many important technological developments -- the computer mouse and flat screen television for example -- ALOHA was developed in the public sector. It was not patented, and was therefor available and widely used by entrepreneurs who used their business acumen to develop popular and profitable products. The important thing was that the technology was out there, enabling the world to communicate more easily, with less cost and in more and more ways -- something hopeful for advancing the well being of people everywhere. But technical awards did flow in Norm's direction for many years. We do not have photographs of all of the award events. Here are a few:

Alytus, 1992

In 1992, a few years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and a year after the breakup of the Soviet Union, Norm and I decided it was possible to visit Alytus. Norm's father was living near us in San Francisco and we wanted to see his birth town before he died.

Reaching the former Baltic Soviet states was not easy. We were told we could not drive a rental car through Poland to reach Russia or the Baltic states. So we traveled by car ferry, first to Denmark and Sweden, then to Finland. We traveled across the Baltic Sea from Helsinki, Finland to Talinn, Estonia and then drove through Estonia and Latvia into Lithuania.

1992 was a difficult time for the Baltic counties that had for decades been dominated by Soviet Russia. This was a year after the breakup of the Soviet Union, but Russian troops were still stationed at bases in the region. In fact, in Riga, we were directed to a Russian military base, to park our car for the night – it would be well guarded, we were told, for $1 dollar -- by Russian troops who had not yet been ordered home and who still carried their Kalashnikovs. If we left the car on a public street, we were told, we would find we had no headlights, no windshield whippers, and no tires in the morning.

The ex-Baltic satellite countries, short of hard currency to purchase oil, shut down power generators and turned the night sky almost completely dark. We still remember trying to find Riga at 11 p.m. as we drove from Talinn. The only thing that indicated a city, and a hotel, was the small glow from the late spring sky that outlined a single tall building ahead of us. Consumer goods were scarce, gasoline, restaurants and other tourist necessities were almost impossible to find. Infrastructure was crumbling, except for a highway that went from Talinn to Riga and on through Lithuania to Kaliningrad. The highway was largely unmarked, built by Soviet Russia and clearly intended for military use -- and in 1992 no road maps were available.

But, with the help of an unemployed Latvian ex-police captain, who we met in a Riga hotel -- once a Russian Intourist hotel – we made our way to Alytus.

Before we left San Francisco we had asked Norm's 90 year old father, Eddie Abramson, what we should look for in his home town. Eddie had severe short term memory loss by the time he was 90. But his long term memory was still intact and he told us about his family and the small town he remembered when he left Alytus in 1922.

Above: Norm and I took pictures of each other at the side of the road near the Baltic Sea on our way from Talinn, in Estonia to Alytus in Lithuania.

But of course Alytus was not the town Eddie had left in 1922. Under post World War Two Soviet domination the town had become an industrial city of drab factories and large blocks of Soviet style apartment buildings. Few of its old neighborhoods were left intact. Identification and marking of memorial sights honoring victims of the Holocaust were nowhere to be found. We saw almost nothing of old Alytus as it may have looked at the time the five Matskevitch siblings immigrated to the United States.

The only building we recognized from Eddie's description was an old church. The church was undergoing some reconstruction, but Eddie had remembered the color of the paint -- and that remained the same.

We saw little. But standing in Alytus, where one of our four immigrant parents was born, was a humbling experience for both of us. Below are a few photographs of the signs that directed us and of what was left of old Alytus, taken in the spring of 1992.

Ellis Island, 2008

Fifteen years after our Alytus trip, when we were in New York City, we visited Ellis Island, where all four of our parents had first entered the United States.

Between 1892 and 1954, Ellis Island was the first destination for most immigrants. It was there that papers were processed and, at times with greater or lessor rigor, health and mental health was assessed. Gradually, as air transportation replaced ship transportation, Ellis Island evolved into a museum that celebrates American immigration. But the laws and quotas that often affected the flow of immigrants into the United States from one part of the world or another are not ignored in the museum exhibits or literature.

Restrictive immigration laws and the unequal application of rights are not new to the United States. To name just two of many: in 1882, just 4 years before the Statue of Liberty was dedicated, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. In 1924, after years of increasing resistance to an influx of Southern and Eastern European immigrants (largely Italians and Jews) Congress passed quotas that diminished the ability of those groups to enter the United States.

In 2008, Norm and I stood in the reception hall on Ellis Island and looked out at the Statue of Liberty. Shimsel and his siblings, our parents, and most of our aunts and uncles, along with many other Halborn descendants and the millions of others who passed through the immigration lines at Ellis Island have done the same thing.

The Statue of Liberty, and Emma Goldman's poem at its base, have never been a completely reliable reflection of reality. But they remain a reliable reflection of a core American value that has continually renewed America's dynamism and creativity.