Fighting With A Camera

In January 1950, Henry Freulich came to my high school graduation. After the ceremony he joined me, my mother, father and sister, for dinner. I remember the evening vividly. Henry was my oldest first cousin — twenty six year my senior.

Henry Freulich was the son of Jack Freulich and the grandson of Isaac Freulich and Nisla Halborn Freulich. He was born in April 1906, and as far as we know he was the first Halborn descendant to be born in the United States. He had begun working full time 10 years before I was born. I saw him now and then while I was growing up. He was always cordial and friendly, but the visits were rare — Henry was a busy man, working long hours and with a full and adult social life. His attendance at my graduation was unusual and surprising and both the evening and Henry's conversation were memorable.

Henry was clearly very proud of me — I had graduated high school at the age of 17 and had been accepted to the second class at Brandeis University. At dinner that evening he told me he regretted his own lack of a formal education. He had left high school at 16, without graduating, he said, partly at the urging of his mother, who was not as impressed by formal education as by an offer of a paying jobs a still photographer from Universal Studio’s owner, Carl Laemmle. Don't stop for anything, he told me. Get as much education as you can.

I considered Henry a well educated man. And he was. But his education was completely informal. It came from his own extensive reading and his own intense desire to learn about the world. So it surprised me to hear how much he regretted his incomplete formal education and how passionately he urged me to complete my own.

From the Bronx to Hollywood

Henry Freulich was born in New York City on April 14, 1906. His parents lived at that time in a small apartment on St. Marks Place on the Lower West Side of Manhattan. By the time of the 1910 Federal census, they had moved to a larger apartment in the Bronx. It was there that he first met his uncle, Roman Freulich, who was just 8 years older than Henry. The two became more like brothers than uncle and nephew, and their close relationship continued for the rest of Roman's life.

Late in 1918, when Henry was 12, Jack Freulich accepted a job as head of the still department at Universal Studios and the family moved to California. Then, in 1922, when he was just 16, Henry left school, accepted Carl Laemmle's offer and took up a new life as a still photographer at Universal.

Later in life Henry discussed his early start in the film industry:

"One night when they were shooting night scenes on the back lot, I went out with my Graflex and made 'stills in action' . . . My stills were shown to Carl Laemmle, who promoted me to Graflex still photographer on the Hunchback company. I continued at Universal as a regular still photographer and doubled as an assistant cameraman, as required of all stillmen at Universal."

The backlot was the set for Universal's silent film production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, staring Lon Chaney, The quote can be found on the Internet in several obituaries written after Henry's death in 1979.

Henry had been given a Graflex camera for his sixteenth birthday in April 1922. The next summer he obtained a temporary job as an office boy on the Universal Studio lot. The job gave him the chance to bring his new camera to the studio and to use it for taking stills. He did not anticipate that it would lead him to a full time job, or to leaving behind his formal education.

Universal

Most of Henry's early work as a still photographer has disappeared — a victim of the low value placed on photography that helped publicize the early films. Much of it was destroyed when studio executives believed that, along with the motion picture films themselves, it had outlived it’s initial commercial value. Considering the flammable nature of the nitrate film used during most of the first half of the 20th Century the destruction no doubt seem wise.

The same is true for all of the photographic work produced on the Universal backlot or, for that matter, on other studio sets during the early years of silent films: almost no still photography survives, and, with few exceptions, the remaining examples that exist today give no clue as to who the photographer was.

Luckily, a few dozen stills from the Hunchback set are among the rare exceptions and can still be found online, including a few night shots. But neither the night shots nor any of the other surviving stills from the production can be identified as Henry’s work — or, for that matter, as the work of any other photographer. The four shown here may be Henry's work, though we have no way to verify this.

Henry began working full time at Universal in the summer of 1922, well before his 17th birthday and worked closely with his father, Jack Freulich. His employment at the studio overlapped that of his uncle, Roman Freulich, who joined the company in mid 1924. The three Freulichs had formed a close bond during the first years of Roman's stay in New York City, from 1913 until Roman left to join the British Army early in 1918. The bond continued throughout their time together at Universal and throughout their lives.

Jack Freulich had begun to refine his photographic style in the early 1900s, a world where the term “still” was not yet applied to photography — the term “still photography” would have been redundant. Henry’s apprenticeship, along with that of his uncle, Roman Freulich, took place in a different world — a world of motion where “still photography” appropriately defined the role of the still as an adjunct to the commercial production of motion pictures. It is this difference that defined the careers of all three men. Jack remained in the world of the still photograph, refining and perfecting his fine and distinctive style. Roman also remained primarily in the world of the still photograph, though his curiosity and his restless nature pushed him to pursue other outlets for his talent, including the use of motion for his own short avant-garde films. Henry, still in his teens, quickly discovered his interest in the use of motion as a format and, within a few years of starting his career at Universal, began focusing on the art of the moving picture.

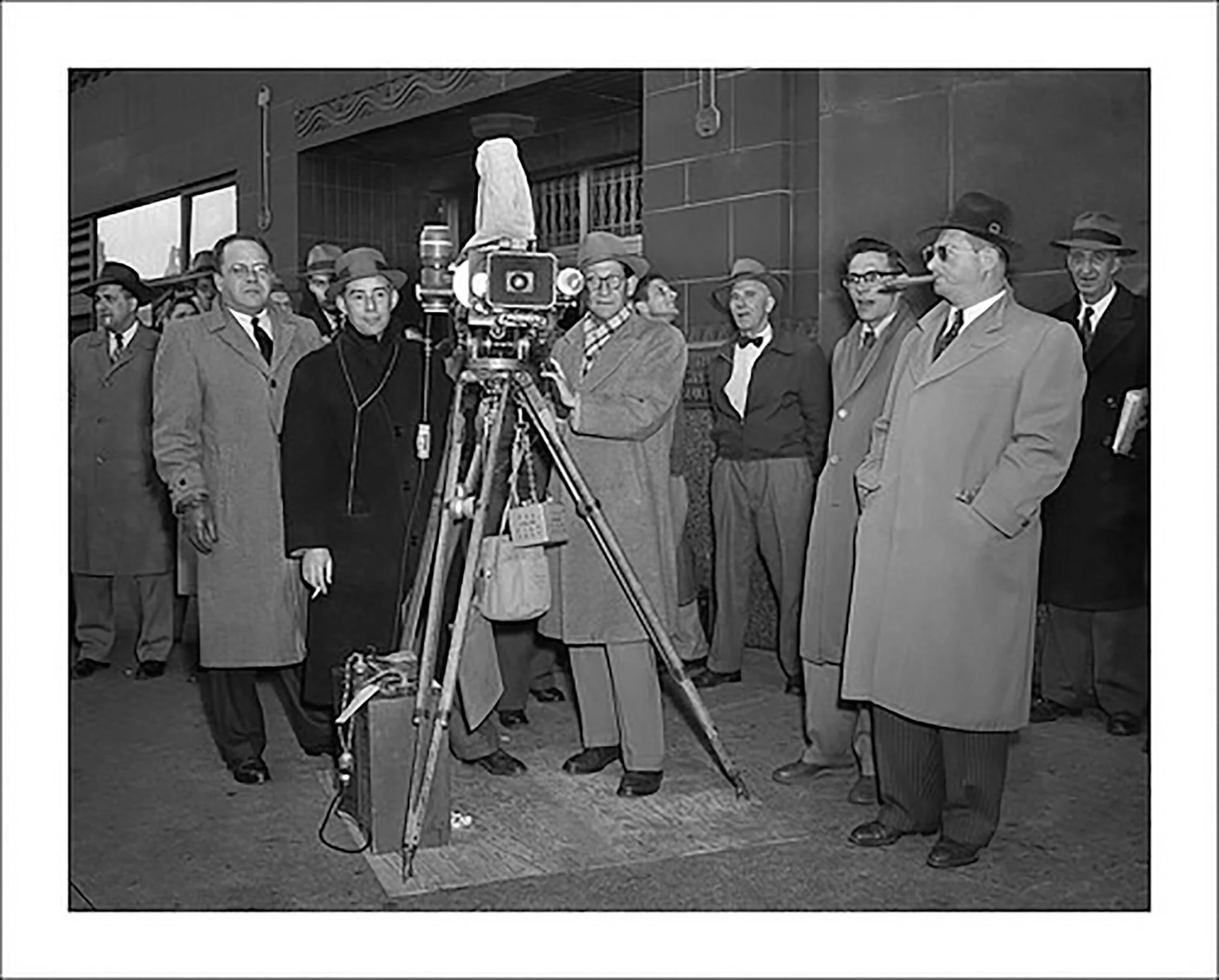

The requirement, Henry noted — that at Universal he had "doubled as an assistant cameraman" — turned into an ambition and a professional goal for Henry and led him to take a job at First National Pictures sometime in the mid 1920s. The picture below marks, more or less, the time when Henry left Universal.

First National Pictures

Despite the interviews Henry had given during his career about his start at sixteen years of age as a still photographer at Universal, the Internet is full of stories that, copying one another, insist on a different scenario. A 1985 obituary for Henry in The Los Angeles Times, for example, says:

He had broken into film work as a still photographer at First National Pictures and moved to Columbia as a camera operator after Warner Bros. took over First National.

Other web sites have copied the inaccuracy almost verbatim:

He broke into film work as a still photographer at First National Pictures, and moved to Columbia Pictures as a camera operator after Warner Bros. took over First National.

The one grain of truth in these statements is that at First National, Henry's work continued, for a time, to be primarily focused on still photography. Most notably, he worked on a series of Colleen Moore films. Again, as is the case with his still work at Universal, little trace remains and few photographs can be positively identified as his. Yet we know that, just as Roman was the first choice for Deanna Durbin films, Henry was the photographer of choice for Colleen Moore. All we can say, then, is that while they cannot be positively identified as his, the photographs, below, of Colleen Moore, are all identified on the Internet as Henry's work.

So far, we have found only two pictures that were signed by Henry and therefore can with confidence be identified as his work. The first is an on-set still of Colleen Moore in the 1926 film Twinkle Toes; the second is an informal photo of Silvano Balboni, June Mathis and another women taken sometime in the mid-1920s.

Cinematography

In 1929, after seven years at Universal Studios and then at First National Pictures, Henry's name was beginning to appear in film credits as a cameraman.

The on-line film data base IMDb.com lists Henry's two first motion picture credits, unsurprisingly, as two releases starring Colleen Moore — Smiling Irish Eyes and Footlights and Fools. Probably his role at this time was as an assistant cameraman but he may also have contributed work as a still photographer on both films. Both films were produced on the First National Pictures studio lot in San Fernando Valley. Both were distributed by Warner Brothers.

Poland and the World

The 1930 census data for Henry states that he is employed as a cameraman and that he works in "motion pictures". In the same census his father, Jack, is listed as a photographer, also employed in "motion pictures." Surprisingly, though Henry had by 1930 been earning a good salary since 1922, he is still listed at the same address -- his parent's home at 6834 Odin Street, in the Hollywood Hills.

At First National Pictures, where Henry worked, things were rapidly changing. Two years earlier, in 1928, rival film company Warner Brothers had begun the process of taking over First National by acquiring the Stanley Company of America theater chain, which was partially owned by First National. Then, in 1930 Warner Brother's took over the First National Pictures studio in the San Fernando Valley. As was to happen six years later at Universal, the transition period caused a fair degree of chaos and uncertainty for studio employees.

For Henry, it was time to take a break. Whatever his reasons —and there were probably many — he decided to leave Hollywood. According to an article he later wrote he headed for Europe with the intention of seeking employment as a cinematographer in Germany.

I don't know how mature or how sophisticated Henry was in 1930. By our standards today, at 24 he had lots of growing up ahead of him. He had escaped the economic chaos that followed the stock market crash in October 1929, as had most of the film industry, which continued to churn out cheap entertainment for masses of people. He had been fully employed in a demanding and time consuming trade since he was 16, which under other circumstances might have provided him with considerable opportunity to mature. But his education was incomplete, he had no foreign language skills, and no knowledge of employment restrictions in other countries. He had little time to follow world events and probably very little knowledge of the economic and political chaos that was worsening in Europe and the United States. And he had lived in his parent's home his entire life. So his choice of Germany in 1930 seems a little naive. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1930, Henry took off for Europe.

Jack Freulich also traveled to Europe in the spring of 1930. Whether he traveled solely to visit his family in Poland or for the dual purpose of seeing his Łódź family and keeping tabs on his only son is something we do not know. Nor do we know if the two traveled to Europe together — ship manifests for outbound travel from the United States are not readily available. What we do have is three types of information about the trip: photographs taken in Łódź, Poland in April 1930, the return trip ship manifests for Jack and for Henry, and a short article Henry wrote for the professional magazine International Photographer, after his return to Los Angeles.

The photographs tell us Henry and Jack both visited Łódź and that they did so at the same time, in the early spring of 1930. The ship manifests for their return to the United States tell us they traveled home separately. Jack, with his major responsibilities at Universal, did not stay in Europe for a long time. He traveled home aboard the S.S. Europa, leaving Bremen on May 6, 1930 and arrived in New York on May 14, 1930. Henry, without any major responsibilities and possibly without a job to return to in Hollywood, traveled home aboard the S.S. President Pierce, leaving Yokohama on July 2, 1930 and arriving in Los Angeles over a month later, on August 10, 1930.

In his article, which was printed in October 1930, Henry wrote:

Six months ago I decided to take a trip to Europe with a double intention. The first was to obtain employment in Germany whereby I might gain some training in the photographic work for which the German technicians are famed. At the same time this appeared to be a grand opportunity to see a little of the world.

Henry, who had never before needed to look for employment, was quickly disabused of the practicality of his first goal:

After being in Germany for three days I learned that work was not easily to be found, especially for one who was unacquainted with the German language. Therefore, I changed the trip into a purely pleasure venture and proceeded to enjoy myself and see the sights.

The first thing I did was to purchase a Leica camera, one that uses motion picture film and makes thirty six pictures without reloading. Germany, Austria, Czecho-Slovaka, Italy, Switzerland and France were the countries that I toured, all of them interesting from both a photographic and a tourist viewpoint. I "did Europe" in three months. I was on the go all the time, not missing an hour from the steady purpose of viewing the wonders of these countries.

Two of Henry’s first Leica photographs showed up over a year after Henry's trip in the July, 1932 issue of International Photographer, the professional magazine of Hollywood still and motion picture cameramen.

It is not possible to say why Henry failed to mention Poland off of his list. Possibly the visit was outside the scope of his short article. Possibly he felt that part of his trip was too personal to include — he had to be aware of his father's concern for his Łódź family. But we do know from a few family pictures, probably taken with his Leica, that he spent time in Poland — certainly in Łódź, probably in Warsaw as well.

The family photographs are still with us. The first, below, was taken in the courtyard of his grandmother's apartment building at No 2 Piramowicza Street in Łódź. From left to right, the photo shows Henry's cousin Rafal, his aunt Sura Rifka, Jack, Henry's grandmother Nisla, Henry, and his aunt Helena. The second shows the same group posed in the garden outside the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, a short walk from his grandmother's apartment.

Certainly the visit was personal. For Henry it was his first meeting with his grandmother, two living aunts and at least one first cousin. And certainly, for a young man growing up in New York and Los Angeles, living in an upper middle class neighborhood of professional people and exposed for years to the fast paced atmosphere of Hollywood, it had to be both emotionally and intellectually challenging to meet close relatives with whom he shared neither background nor language. Whatever his reasons, Henry left this part of his six month round the world trip untouched.

The rest of Henry's article deals with his travels in Asia.

Then I caught a boat from Genoa, Italy, to Shanghai. This boat was a combination freighter and passenger boat which made stops at Colombo, Singapore, Java, Manila and Hongkong. I arrived in Shanghai five weeks later. I had thought Europe was wonderful, but found the Orient impressed me much more. . . The most interesting thing was the people. In Peking one feels he is in a world two thousand years ago. And I went crazy making pictures.

He was right —he exposed 2,500 35mm negatives on his six month journey. Unfortunately, the family collection has only a few — the few he allowed someone else to take of his family in Łódź.

In the remainder of his article Henry briefly describes a typhoon that had him first "delighted with the prospect of experiencing one" but left him, after six days, "wishing I were dead." He comments that Japan was "truly a tourist's delight" and then notes:

The reason I am writing this is that because of having these experienced these wonderful things myself, I feel that other young fellows also should experience them because of their wonderful educational value and broadening influence.

Then he concludes with one of the most important lessons he learned:

So far as working away from home is concerned, this is very impractical unless one has a job lined up before leaving the country. The best thing to do is to work hard in Hollywood, save money, then take a good long vacation. It costs a little money, I admit, but the advantage gained is worth many times the amount expended.

Returning to Hollywood

After completing his trip, Henry went to work for Columbia Pictures. But credit for motion picture filming, as with still photography, seems to have been somewhat random during the early 1930s. This may explain a large the gap in the IMDb.com database: between 1930 and 1934 there is not a single motion picture camera credit listed for Henry in that database.

Regardless of the gap in the records, and in spite of his six months away from Hollywood, it is clear that Henry continued to acquire considerable experience behind the motion picture camera. Before he left for Europe Henry had been well on his way to establishing himself as a cinematographer. And four years later — almost the very same years when there is not a single credit for Henry in the IMBb.com database, he became the then-youngest ever member of the American Society of Cinematographers. Despite the lack of credits it is clear that Henry did not achieve that distinction without working as a cameraman on a significant number of motion pictures between his return from his world circling trip and the time membership was awarded in 1933. At 27 years of age, in 1933, Henry had become a full-fledged, qualified director of photography.

A word about the hierarchy within cinematography may be useful here even though, much like the distinction between still photographers and portrait photographers, that hierarchy was loosely defined and often ignored in the Hollywood of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Motion picture assistant cameramen, sometimes called second cameramen, took charge of camera operation under the direction of a cinematographer or a director of photography. The assistant cameraman was, for the best camera operators, an apprenticeship and often a stepping stone to work as a cinematographer. The term cinematographer was interchangeable with the term "director of photography". It described the same set of people, though sometimes cinematographer was used when films required only a single photographer, with or without an assistant, while the term "director of photography" was used for major productions requiring multiple cameras.

Henry continued working at Columbia into the 1950s, turning out a huge volume of film work — as many as 10 and 11 full length features every year. Ten films for which Henry served as cinematographer were released in 1942. Most were made during 1941 or the early months of 1942. Then a second break occurred in Henry's Hollywood career — his name is not listed as cinematographer in another film until 1946.

War

In the early months of 1941, almost a year before the United States formally entered World War Two, the impact of the war in Europe once again came home to the Freulich family. Henry received word from his maternal uncle, Wolf Arenstein. The family — Wolf and Mira Arenstein and their two children, Henry's first cousins, 14 year old Michal and 12 year old Karel — had escaped from Warsaw at the end of 1939 and spent more than a year extricating themselves from Europe and then from the middle east. They had finally managed to reach Japan and were about to begin a voyage from Yokohama to the West Coast. They needed help gaining entry into the United States.

Henry, along with his uncle, Roman Freulich, went to work.

United States immigration restrictions, even in the face of Nazi persecution of Jews, were difficult to overcome. But somehow the two men were able to gain six month visas for the Arensteins. Then they were able to guarantee that the family would not become a financial burden and managed to change the visitor visas to permanent residency for the four. The story of re-connecting with Karol Arenstein's family can be found in our book on the Halborn family. Here it is enough to say that for the two Freulich's the war had come early, with the German invasion of Poland in September 1939.

Less than a year later, on December 7, 1941, Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States was at war. Full engagement began on December 11, 1941, when Germany and Italy declared war on the United States.

Henry's active service began seven months later, on July 30, 1942. He would remain on active duty for four years, starting at the rank of Private First Class in the United States Marine Corps. Duty rosters, kept with great consistency during the war years provide some insight into the four years Henry spent away from Hollywood, though wading through the frequently used multiple acronyms of military records can be difficult.

In October, 1942, following his initial training Henry, was promoted to First Lieutenant and assigned to a photographic unit as a cameraman. His first task appears to have been assessing and purchasing Marine Corps photographic equipment that would presumably be used both for training purposes and for combat. He was assigned to temporary duty on the east coast with a mission to "inspect certain photographic equipment required" by the Marine Corps and "for the purpose of obtaining certain photographic equipment needed by MC Photographic Section."

Henry's name appears in Marine Corps rosters again five months later. In April 1943 he is listed as a captain. For the remainder of 1943 and the first part of 1944 he traveled back and forth between San Diego, California and the East Coast, evaluating and acquiring equipment and producing Marine Corps training films — important and necessary tasks, to be sure, but probably not what Henry had expected when he first enlisted.

Okinawa

By mid-1944 Allied forces in the Pacific had progressed far enough to begin preparing to invade Japan. In the fall of 1944, the Sixth Marine Division was organized from several existing Marine infantry regiments and special purpose battalions. The new division was sent to Guadalcanal Island in the Solomon group for specialized training intended to ready troops for the final invasion and occupation of Japan. The invasion was to begin in the Ryukyu Islands —Okinawa and a number of smaller outlier islands to the south of Kyushu. These smaller islands had been Japanese territory since 1879. From there the plan was to continue north to Japan's main islands. Henry was part of the Sixth Marine Division. His role was to cover combat missions for the purpose of providing commanding officers with intelligence on enemy positions.

With a fierce naval operation still in progress, the Sixth Marine Division landed in Okinawa in the first wave of Allied troops. The Muster Roll for Henry reads: ". . . arr.[arrived] at Okinawa, R.I. [Ryukyu Islands] aboard PA 54 and disemb [disembarked] in initial landing operation against the enemy on that island." The date was April 1,1945. The battle for Okinawa did not end until June 22, 1945.

Okinawa was and remains, a part of Japan proper and its population was, and remains, Japanese. Perhaps for this reason, when invasion was imminent, the Japanese military organized the male population of the island into fighting units. This included all middle school boys — supposedly volunteers, but actually conscripted into front line units. About half of those boys lost their lives during the fighting. One of only two photographs we have of Henry during the war shows him inspecting some of the young boys who survived, along with their older commanding officer.

The battle for Okinawa was the bloodiest of the Pacific war, with over 14,000 Allied deaths and over 77,000 Japanese deaths. The ferocity of the battle was part of the reason that the United States decided that a land invasion of the main Japanese islands would be disastrous and, instead, opted to use two atomic bombs to force Japanese surrender.

Henry's role with the Sixth Marine Division was to carry a camera, not a gun, and to provide front line intelligence that would help the Allies to dislodge Japanese troops. After the battle Henry was awarded the Bronze Star, The citation speaks for itself:

On August 6, 1945, The United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, on August 9, 1945, a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945.

The American use of atomic weapons, the first and last such use in war, is still controversial. The United States believed then, and still contends that the loss of life would have been greater had America chosen to conduct a land invasion of Japan.

Home

In April, 1946, Henry was demobilized, returned to California and took up his career, once again at Columbia Pictures. In the early 1950s, while still working most of the time at Columbia films, he began taking jobs elsewhere, many of them for the newly emerging television industry.

Despite the gaps in his career as a cinematographer —the first in the early 1930s and the second, longer gap during World War Two — Henry Freulich compiled a remarkable list of film credits as cinematographer or director of photography: over 200 feature films and over 20 television series. He worked on horror films and romances, comedies, dramas and war stories including, ironically, a film called Okinawa that drew heavily on camera footage shot during the Okinawa campaign. Some of that footage was probably taken by Henry himself during the war. He served as cinematographer on most of the Three Stooges and Blondie films, and on some westerns that are, today, considered classics. Between 1952 and his retirement in 1969 he served as cinematographer or director of photography for multiple episodes of Schlitz Playhouse, Cavalcade of America, Dennis the Menace, The Mothers-in-Law, I Dream of Jeannie, Alcoa Theater, Shirley Temple Theater, The Beverly Hillbillies, and over a dozen other television series.

Henry retired in 1969. He died 16 years later, on December 3, 1985. For a while, during his career, he seems to have thoroughly immersed himself in the active Hollywood lifestyle. His friends and neighbors were Hollywood people and celebrities. He married three times. A wartime marriage to actress Kay Harris lasted only a short time. His second marriage, to Sandra Breaux Perry, ex-wife of tennis star Fred Perry lasted longer, but dissolved a few years after the war. I remember their home on Mulholland Drive, overlooking Los Angeles. The home was sold to film star Ida Lupino after Henry’s divorce. Ida Lupino and Sandra Perry and Henry and neighbor Boris Karloff were friends. He married Adele Roy, his third wife in 1961, when he was 55 years old, and remained married for the rest of his life. He had no children.

Henry had come to my high school graduation less than four years after he returned from his service in the Marine Corps, We had never discussed his feelings about his Hollywood work, and I do not know if, like my father, he harbored regrets that he had not accomplished more with his life. I cannot question the professionalism of his cinematography. His skill and judgment were well respected. He was, throughout his working life, always in demand. The massive volume of his work speaks to that. But his regrets about his own lack of formal education also speaks volumes.