Roman Freulich, Innovator

Introduction

Early Hollywood still photographers often kept track of their work by taking home a few prints from some of the films they covered. Roman Freulich began to do so in 1928, four years after his career as a Hollywood still photographer began.

He continued the practice on and off for more than 40 years, until he retired in the early 1970s. Like many other still photographers, he realized that unless he saved a few pictures, the lack of attribution common in the early days of filmmaking would leave him without a record of his career.

Roman’s collection never covered more than a small percent of the work he produced. But that work was voluminous. After his death in 1974 the family gradually donated about 90% of his collection to several museums. Though we kept careful records, the photographs were donated before high quality home scanning was available. Nevertheless, between photographs currently in our possession, photo books that Roman produced, and cooperation from museums, it is possible to verify every photo reproduced in this story as Roman’s work (with the exception of pictures taken of Roman by others).

This post is, therefore, more loaded with visual material than most post in our Halborn web page. The pictures and a lifetime of family memories help inform this story about the sixth and youngest child of Isaac Freulich and Nisla Halborn Freulich.

Leaving Częstochowa

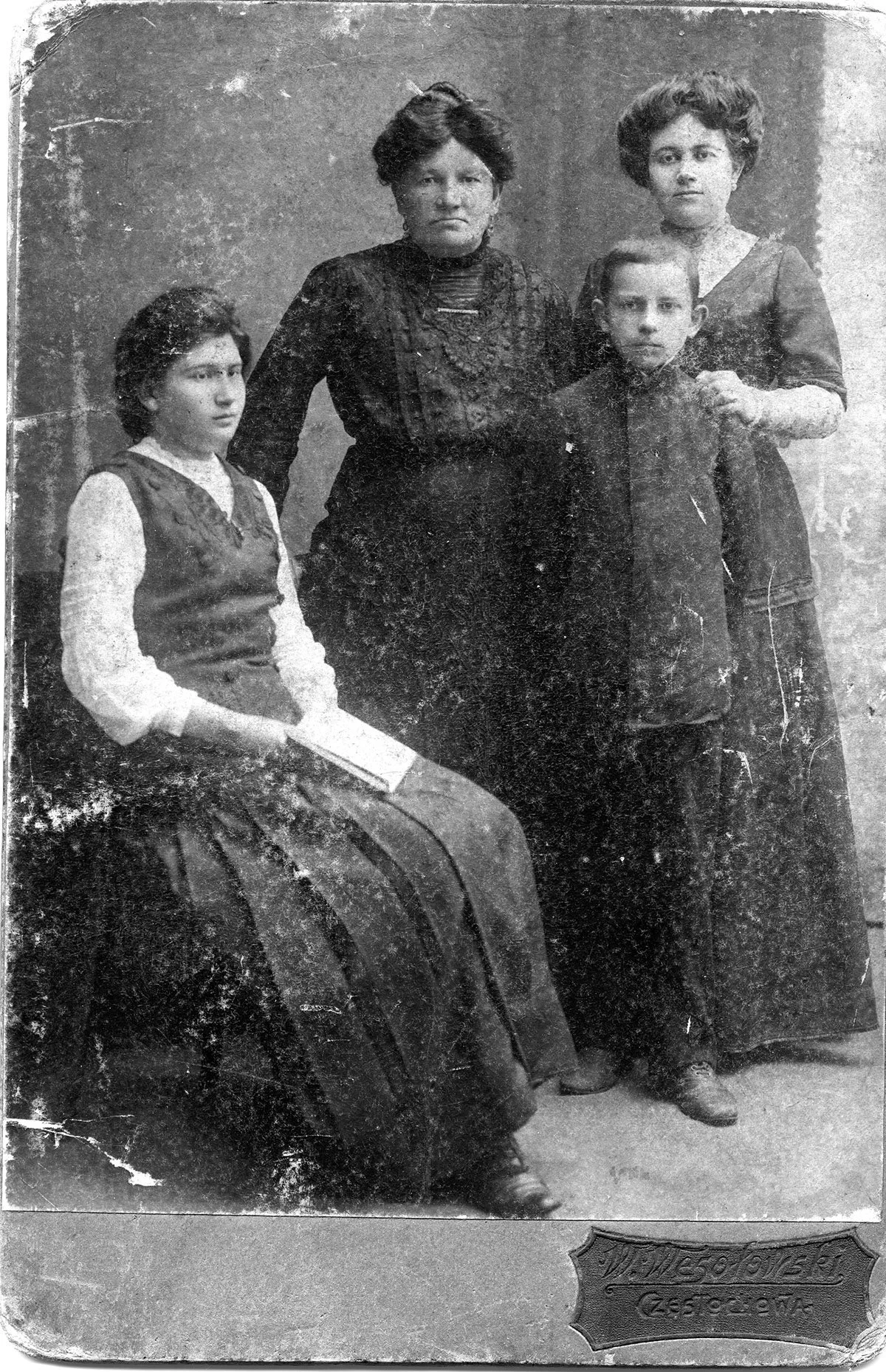

Roman Freulich was born on March 1, 1898 in Częstochowa, Poland. His parents were no longer young — Isaac Freulich was probably about 50 in 1898 and Nisla was 41. At Roman’s birth, his oldest sibling, his sister Sura Rifka was 20. His oldest brother Jacob, was 18.

As the youngest male child, Roman was relatively privileged. He attended both grammar school and gymnasium — the equivalent of an American high school. He was quick to learn and did well in his studies — he became proficient in Russian, Polish, German and Yiddish — and acquired a taste for art, literature and classical music.

Roman also developed a strong anti-Tzarist passion for justice. And, as a young teen he became active in the Jewish Socialist movement. Probably against the wishes of his mother and his father he began distributing literature for the movement in his after school time.

When Roman’s oldest brother, Jacob (Jack in America), immigrated in 1901, Roman was about three years old. Though he had little memory of his brother, Jack’s immigration proved fortuitous when, late in 1912, Roman’s after school political activities became worrisome. With Jack’s help, a quick exit from Częstochowa and from Poland seemed both necessary and possible.

As an adult Roman became a prolific story teller and his experiences leaving Poland and aboard the ship traveling to America became the source of many entertaining yarns that varied in their details with each telling. But one way or another, at the age of 15 he crossed several borders on his own and met with his father and older sister, Paulina, somewhere in Western Europe. Together the three boarded the SS Noordam in Rotterdam on July 5, 1913, arrived in New York nine days later, and headed for Jack Freulich’s home on Kelly Avenue in the Bronx.

New York and Palestine

Jack’s apartment was crowded during the months after Isaac, Paulina and Roman disembarked. Roman recalled that for a time his bed was a makeshift pallet on the kitchen floor. But Isaac and Paulina soon found employment in the garment industry and the three newcomers moved to an apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan — a neighborhood still dominated by sweatshops and dark, crowded tenements, but one with easy access to some of New York’s best educational resources.

Roman was small for his age but he was not timid and he was a quick study. He had picked up sufficient English in his nine days aboard the Noordam and his time living with Jack to make his way in New York. And he quickly discovered that he could advance his education without any cost to his family. He attended classes at both Cooper Union and the Baron de Hirsch Trade School. With Jack’s encouragement and support, he continued his classical education —improving his grasp of the English language and feeding his love of literature and the arts. Nor did he ignore the likelihood of needing a trade: he obtained certification as a qualified electrician.

Served by his quick wit and amiable nature, he made friends among his fellow students, most of them Eastern European Jews who, like Roman, were taking full advantage of what was then a free education for qualified students living in New York.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914, a year after his arrival in America, discussions among Roman's friends began to center on the Russian Empire. The dialog was intense: Should they, or shouldn’t they, enlist to fight with the Allied nations, which included Tzarist Russia? Most of them had only recently fled the Tzarist empire — why would they now fight on the same side?

In 1917 the Russian Revolution brought an end to the problem and the debate. Tzarist Russia was overthrown and was no longer a partner in the war or an obstacle to joining the Allied cause. And as far as many young Jews were concerned that cause was bolstered in November, 1917 by the Balfour Declaration — the British government commitment to support a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

The history of how the British government formed several all-Jewish battalions within the Royal Fusiliers and sent those battalions to fight the Turks in Palestine is a fascinating one, but beyond the scope of this story. Here, suffice it to say that Roman, along with thousands of young Jewish men in America and from around the world, enlisted in the British Royal Fusiliers. By spring, 1918, he and hundreds of other young Jewish men living in New York crossed the northern border between the United States and Canada to begin training, then traveled to England, then across the channel to France and overland to Italy, where the troops embarked for Egypt. As part of the 38th and 39th battalions of Royal Fusiliers, they fought in key battles in the Jordon Valley, and captured the Umm Shart Ford across the Jordon River, opening the way for British troops to move into Damascus. Then, after the armistice, the troops, charged with keeping the peace, helped defend Jewish settlements and the Jewish community in Tel Aviv against Arab raids.

Roman took a small camera with him when he left New York for training in Canada and carried it throughout his enlistment. But contrary to the conclusion of some writers, he did not serve as a photographer while in the Jewish Legion. It was probably his interest in taking pictures — no doubt stimulated by Jack Freulich — and his interest in experimenting with sun processing and printing that is responsible for generating this misconception. Years later his former comrades often told stories of the frequency with which his camera would appear and, even more vividly, recalled the frequency with which strings of negatives and paper hung outside their tents.

Roman’s service in the Jewish Legion foretold his willingness, throughout his life, to take on causes he believed in. Similarly, the fact that he took along a camera and experimented with developing and printing photos foretold his lifelong interest in exploring new directions for his work.

Hitchhiking to Hollywood

In December 1919 Roman returned to New York aboard the SS Cedric along with hundreds of other returning Jewish Legion veterans. He was discharged from British service on January 11, 1920 as “surplus to military requirements.” His discharge papers further record that British army doctors found him “not having suffered impairment since entry into the service.”

Roman remained in New York for a few months — long enough to visit his father and sister and to be recorded in the 1920 United States Census as living at their apartment in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Then he traveled west across the United States — not once but twice.

The SS Cedric manifest records that Roman’s final destination upon returning to the United States in 1920 was not New York. It was “Brother, J. Freulich, 1622 Las Palmas Ave. Hollywood, Cal.” Clearly he intended to move on and establish a new life for himself in Los Angeles, probably with a job as a Universal Studios photographer in mind.

The reunion of the two brothers, following Roman's first arrival in Los Angeles, was recorded at Jack’s Universal portrait gallery with a full length photograph of the two brothers (above).

The photo is notable for two reasons: First, Jack is clearly elated — of the several dozen photographs we have of him, this is the happiest. He seems delighted to have his brother with him. Second, Roman, while he too seems delighted to be in California with his brother, looks startlingly different than the healthy young man who had left for Palestine less than two years earlier. His suit hangs awkwardly from his bones, his face is thin, and his whole body appears to have dwindled.

Something was clearly wrong and Jack knew it. Rather than putting his brother to work learning the professional still photographer’s trade that would require him to lug around the huge cameras used on sets in the 1920s, Jack sent his brother for a physical checkup. Far from “not having suffered impairment since entering into service” he was diagnosed with an advanced case of tuberculosis.

In October 1920, Jack checked Roman into the Barlow Tubercular Sanatorium in Chavez Ravine near downtown Los Angeles. Roman spent the next 15 months of his life there — several months longer than the time he had spent in the British Army.

When Roman left the sanatorium In January, 1922, he was not yet strong enough to take on the job of still photographer. He moved to Pasadena, then a rural suburb of Los Angeles, and took a position as a librarian in the quiet confines of the Huntington Library. He remained there into late 1923, working among books — something he had always loved — and sharing a sunny suburban cottage with a friend.

It was at this cottage, in March 1922, that Roman threw a birthday party for himself and met his future wife, Katia Merkin. Then, in the winter of 1923-1924, Roman returned to New York to meet Katia’s mother and introduce her to his father.

How Katia — my mother, who was also an immigrant, and who had worked in the garment industry in New York since the age of 12 — found herself in California is another story, as is the story of their cross country romance.

In New York City, on January 17, 1924, Roman Freulich and Katia Merkin were married. Within days they donned knickers and small backpacks and were on their way — hitchhiking back to California.

The adventure took them months. The two zigzagged across the country, visiting acquaintances here and there, spending time with Roman’s brother Henry, who lived in St. Louis, catching tourist attractions and enjoying museums and natural wonders. They stayed sometimes in rough and dusty tourist cabins. More often they camped out.. They caught rides — sometimes for only a few miles, sometimes for a day or two. And sometimes they ended up sitting besides a deserted road for hours before a single car came into view.

The cross country trip provided Roman with another opportunity to practice his photographic skills and to use the same small camera he had carried during his Jewish Legion enlistment during World War One. The trip also provided Roman with another source of stories which he proceeded to mine for the rest of his life.

After his long stay in the tubercular sanatorium Roman needed months of convalescence. The delay in beginning his Hollywood career had been a long one — almost four years in length. But ultimately it proved to be a happy one. In the spring of 1924 as their leisurely but adventuresome honeymoon came to an end, a job as a still photographer at Universal was waiting for Roman in California.

Universal Studios

Roman worked at Universal Studios for more than two decades, from mid-1924 until 1945, when he took a new position as head of the Republic Studios portrait and still department. During his first 12 years at Universal, he worked closely with his brother and undoubtedly learned a great deal about production work, publicity shots and portraiture. As usual, he was a quick study and his early work quickly showcased his talents. We do not have many of those early photographs in our family collection. Because the names of still photographers did not begin to be included in film credits until late in the 20th century no complete or accurate record exists of all the films he covered during his long career. But there are enough stills available both in our collection and online to illustrate that career.

Among the early silent films Roman covered as a still photographer and also, at times, as a portrait photographer, was the 1927 production, Surrender, the 1928 films The Man Who Laughs, and The Foreign Legion (which is among the many lost silent films), and the original 1929 silent version of Showboat.

The available record for the 1930s is slightly better than for the 1920s, but it, too, is far from complete. We know that Roman worked on a number of horror films, and that his work included this iconic portrait of Boris Karloff in his Frankenstein makeup from The Bride of Frankenstein.

Roman covered the 1931 Bella Lugosi film, Dracula and the 1934 film The Black Cat. He also worked on most of the horror films directed by James Whale, who has become something of a cult figure recently among horror movie fans. Whale directed the 1933 Claude Raines film, The invisible Man, as well as several Boris Karloff films, including the 1930 film Frankenstein, the 1932 film, The Old Dark House, and the 1935 film, The Bride of Frankenstein. A selection of photographs from these films is shown below.

While James Whale is still celebrated for his horror films, those films were not his only directing efforts. He was one of Universal’s most prolific working regulars, and took charge of production of a number of outstanding films, including the 1930 film Waterloo Bridge and The Road Back, the controversial 1937 sequel to the Academy Award winning 1930 production All Quiet on the Western Front. Roman worked on all of these, as well as serving as the still photographer for All Quiet on the Western Front, which was directed by Lewis Milestone.

(A side note: Roman is not credited on the Internet for his work on any of these films, though he is given credit for working as a still photographer on the 1920 silent film, Outside the Law. But, Roman was probably confined to Barlow Tubercular Sanatorium at the time that film was produced, and did not begin working at Universal until four years after that film was completed. Moreover, there are photographs, signed by Jack, of several of the film’s actors, including Lon Chaney, Jr. and Anna May Wong. Attributing the work to Roman seems to be yet another example of confusion between the Freulich photographers.)

Roman was also a regular covering Deanna Durbin films, which became quite popular during the second half of the 1930s. He was a favorite on Durbin sets from her first full length film, Three Smart Girls, produced in 1937 through Christmas Holiday, produced in 1944.

The largest collection of Roman’s Hollywood work can be accessed at the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Los Angeles. A sample of typical production and gallery stills from the 1930s and 1940s can be found below.

Family

Work at Universal during the 1930s and early 1940s required long hours away from home. The work week was five and a half days long — Saturday was only a half holiday. Location days — or weeks — were often longer, requiring day after day of work from early morning until late into the evening. The eight hour day did not apply during filming.

For my sister and for me, this meant that weeks would often go by when we did not see my father or when we saw him only on weekends or for a moment when he came home and tucked us into bed before sitting down with my mother for a late supper.

And it meant that our summer camping trips were mostly taken without my father. On a Sunday, early in July, he would drive us to the San Bernardino mountains, east of Los Angeles, where we spent many of our earliest summers. He and my mother, sometimes along with an uncle and aunt and cousin, would set up our tent and organize our campsite —helping us stuff our summer mattress covers with fresh pine needles — and he would spend Sunday night with us. But Monday, before we woke, he would be gone, back for a week of work at Universal. Then, late in the afternoon on Saturday we would hear the family car chugging up the hill toward our camping site and my father would appear, usually bringing a treat —a cold watermelon he had picked up along the route, or a bag of fresh cherries. Sunday's were special because he was with us and because, since our car was there, we could travel a little farther than usual from our campsite to a nearby lake to paddle around in the cold water. On Monday morning he would be gone again before we were awake.

Despite his long hours, Roman managed to document almost every aspect of our young lives, both with his work equipment and with an 8mm motion picture camera he purchased before my sister and I had turned 3 and 4 years old. Visits from out of town relatives, family events, our summer camping trips -- everything was documented. The photograph below is typical: taken at our summer campsite in the San Bernardino mountains in 1936.

Roman's understanding of the value of photography went far beyond the workaday understanding of a skilled technician. This is not something that automatically comes to mind in discussing his work because he so often sought out something different to give meaning to his professional life. Especially as he grew older, photography never wholly satisfied his creative urge. Yet the collection of pictures my sister and I were able to retain from our childhood is a gift Roman left us, whether consciously or not. It is a gift that his grandchildren and great grandchildren cherish to this day.

Breaking Out

By the 1930s Roman had achieved considerable respect as a studio photographer. Well before the end of the decade he had earned the nickname “One Shot” for his ability to capture significant moments from film sets quickly and accurately without having to re-shoot and slow production. The same reputation followed him into the portrait gallery, where his work was increasingly in demand.

But repeating the same achievements was not natural to him and the 1930s turned out to be a decade of exploration. Roman had already shown interest in turning his camera away from what was required during movie production — interest in photographing people working on film productions or taking breathers between scenes, interest in scenic shots while on location and interest in people, cityscapes and scenery when away from the studio. In fact, some of those photographs are the ones he most prized — and some are among the few whose borders he signed.

The late 1920s and 1930s was also a time when a few film industry workers began to seek new directions for motion pictures. Roman was among them. In 1933 he wrote a script for a short film. Then he and a few friends — two actors and a cinematographer — scraped together a few hundred dollars, traveled a few hours east of Hollywood to the Mohave Desert where Roman directed filming of a short avant-garde movie called Prisoner. When the film was released a short article appeared in the New York Times that read, in part:

Roman Freulich, a “still” photographer at Universal, has determined to invade the sacred realm of production. Without the use of money in other than carfare proportions, he has made a two-reel subject called “Prisoner,” which local critics and previewers have applauded. The film contains a full score by a symphony orchestra, some of the outstanding photography of the year and a story of unusual quality. The entire effort was written, directed, produced, cut and edited by Mr. Freulich with three friends, George Sari and Jack Rockwell, actors, and King Gray, cameraman, contributing their services.

Other positive short reviews followed, especially in cities around the United States where there were audiences looking for new and thoughtful film experiences.

The group actually made a bit of money — a few hundred dollars — on Prisoner. And within a year Roman had written another script and organized filming of another short avant-garde film. He called the new film Broken Earth. It was the story of an African-American sharecropper, working long hours and trying at the same time to keep his small son alive, Once again the film was the work of volunteers, working on their own time with the money earned from Prisoner covering some of the production costs.

Putting together what happened next involves a certain amount of guess work — but it is educated guesswork, considering the timeframe of events at Universal: It is likely that Universal owner Carl Laemmle saw Prisoner after it was released. And it is likely he saw Broken Earth late in 1935, after Roman had completed editing the film but before it was released. Indeed, Laemmle may have been instrumental in getting Continental Films, which had distributed several Universal films, to distribute the short film. Then, in the autumn of 1935, several trade publications released nearly identical articles announcing that Roman was on the path to a new career. One of those stories, from Hollywood Life, read, in part:

When Carl Laemme announced that he would advance employees at University City, me meant it. Roman Freulich, former still cameraman, submitted an idea for a story to Laemmle and as a result has been taken off his assignment as still cameraman on Hangover Murders, being directed by James Whale, and Freulich is now whipping the as yet untitled story into shape.

Freulich two years ago at his own expense and on his own time wrote, directed and photographed a short subject entitled Prisoner. The film was hailed as an artistic achievement by critics when it was shown in Hollywood at the Filmarte theater. It was also shown widely throughout the United States. . .

He is the brother of Jack Freulich, noted Universal portrait photographer and uncle of Henry Freulich, Columbia first cameraman.

A great many things were going on at Universal at that time: Production had finished on a new version of Showboat in the fall of 1935 and film editing was in progress. Roman had worked on that production as still photographer. And Carl Laemmle had borrowed heavily in order to complete the film, using his ownership of Universal as collateral.

For a few months in late 1935 and early 1936, before Broken Earth was released, Roman was on his way to a new career. Then, in a single month — April 1936 — Laemmle defaulted on his loan and Standard Capital Corporation took over Universal. Lammle was out. Roman’s career as a screen writer came to an end. And Broken Earth was shown in theaters for the first time.

Once again, like Prisoner, the short avant-garde film was favorably reviewed. The April 1936 edition of International Photographer carried the review shown on the left.

And on April 6, 1936,Douglas Churchill wrote in the New York Times:

…Those who have risen to fame and affluence in the industry as the result of artistic endeavor are few. Producers are inclined to overlook individual strivings along lines comparable to the Little Theatre movement, preferring to seek smashing box office epics. Roman Freulich, a still camera man at Universal made a one-reel subject "The Prisoner," two years ago which attained considerable note in the cinema art temples of the land although it failed to be recognized by the cathedrals. As a result of that venture (on which he made a net profit of $200 — which quite amazed him) he recently invested two Sundays and $750 in "Broken Earth" with Clarence Muse as star and the Shaw Ethiopian choir providing background music. All, including players and technicians, contributed their services. Freulich previewed it the other evening before a group interested in both the cultural and the financial aspects of the screen and it was regarded as meritorious by both classes. It shows considerable artistry and provides some stirring moments, too. As a result he has received finances with which to make a series with Muse, based upon daily incidents in the life of a Southern Negro…

Over the next few weeks similar reviews appears in Hollywood Life, Hollywood Spectator, Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. Then, in mid-April 1936 Universal was taken over by Standard Capital Corporation. Broken Earth faded from view and Roman returned to his position in the Universal still department.

Broken Earth resurfaced a second time in 1939, as The Broken Earth, and as the production and the property of Sack Amusement Enterprises. Sack was a company that supplied films to theaters serving African American audiences during the 1930s — a time when the Southern United States was still segregated. How the film made its way from Roman and from Universal to Sack Amusement is not known.

Unfortunately, Prisoner is considered a lost film. Roman retained a copy of his typewritten script, a few reviews, and a single, small card announcing a showing of the film. After a time circulating as a Sack production Broken Earth also disappeared, though a part of it appeared in a film called The Blood of Jesus, written and produced in 1941 by Spencer Williams. Except for that small fragment, Broken Earth, like Prisoner, was considered a lost film. Then, in 1983, a copy resurfaced in a warehouse in the small town of Tyler, Texas — part of a collection of films later critics assumed to have been “created for African American audiences during segregation.” The movies, all originally filmed on volatile nitrate stock were given to Southern Methodist University where they were transferred to safety film and then, in the 1990s, digitized.

The entire collection is available today on a three DVD set called The Tyler Black Film Collection and can be purchased from SMU. The collection editors believed Roman was an African American director and that Broken Earth had been created for an African American audience — a mistake that was easy to make considering that the film was found with a collection of Sack Amusement Enterprises releases. But the editors were not correct about Roman's race or about his intent. The film was made in keeping with his own beliefs, for all races. He genuinely felt that African American history, stories and pain were an integral but neglected part of the American story and needed to be understood by all. Broken Earth was intended as the first of a series that would depict African American life in America in a realistic and sympathetic way.

Coincidentally, on the set of the 1936 production of Showboat, Roman had met and befriended singer and actor Paul Robeson and the two had plans to make several films together, including a movie version of a Seattle theater production called Stevedore, in which Robeson had starred. Their plans were disrupted a few years later by World War Two.

While only Broken Earth has been rediscovered, both of Roman’s film are repeatedly noted in books covering Hollywood’s 1930s avant-garde film movement.

When Roman returned to his old job as a Universal still photographer he was not through with his desire to try something new. And his next opportunity came during the second Deanna Durbin film produced at Universal, which was also the second Durbin film he covered at Universal.

One Hundred Men and a Girl went into production at Universal in 1937. Roman had been experimenting with a 35mm Leica camera and one day decided to try it out on the set. He used the small camera for several days and was so pleased with the results that he left behind his large speed graphic camera — the standard Hollywood still camera at that time — and went to work with only the Leica.

As he did with all his experiences, Roman turned the events that followed into a story that he embroidered a bit more with each telling. But the bottom line was that after a few days, Leopold Stokowski, who (naturally) played the part of an orchestra conductor in the film became annoyed that a tourist with an amateur camera was “click clicking away” on the set and asked that the intruder be removed. The misunderstanding was soon corrected, Roman completed the film carrying his Leica, and Stokowski and Roman became friends.

Roman quickly became an advocate of using small cameras on Hollywood sets, writing articles for professional magazines and noting that his fellow still photographers “seem convinced that nothing good can come of a camera you can stick in your pocket”. The articles themselves were probably not his first for professional and movie fan magazines — another way in which he began to explore new directions.

Then he entered several of his 35mm shots of Stokowski into an international exhibition. and in 1938 he won an award “for excellence in Leica Photography”.

New York, London, Poland

Nineteen thirty six was an emotionally trying year for Roman. It had begun with a new career as a Universal screenwriter and then, coming within a single month, the release of his second successful short film, the takeover of Universal, and the end of that new career. And then, in October 1936, six months after Universal changed hands, Roman’s beloved older brother, Jack, took his own life.

A year later Roman, aware of the increasing threat of Nazi Germany and worried about his family, prepared for a six week leave from Universal. He left Los Angeles in January 1938, carrying with him his 8mm home movie camera and the same small Leica he had vigorously advocated as a fine professional tool. Roman’s first stops were New York City, where he visited relatives, and London, where he met with Paul Robeson and his wife Essie to talk about their still active hopes of filming Stevedore, together. Then he traveled across Europe to Łódź, Poland. The trip allowed him time to take some photographs that clearly justify his advocacy of the Leica as a as professional tool.

Roman traveled through Germany to reach Warsaw and then Łódź. The train ride convinced him that Poland was in trouble and that European Jews were in danger. But how much danger?

He arrived in Łódź in early February 1938. That winter it was hard to find anyone in Poland who was convinced that danger from Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia was real or immediate. No one could imagine that a German invasion was 18 months away or that the Polish Army would collapse within weeks of an invasion. And certainly no one could imagine that Hitler’s anti-Semitic rhetoric would turn into a murderous Holocaust. Even after traveling through Germany Roman probably could not fully imagine what was ahead for his family.

Roman took about six minutes of 8mm motion picture footage on his trip. He photographed his departure from New York as well as scenes in London, and Lodz. Over the years the film became damaged and badly faded. It currently is housed at the Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles along with a digitized version that was eventually made of the footage. About one minute of the film shows his mother, his sister, his nephew and several relatives we cannot identify. That clip has been posted on this website.

Roman's reunion with his family was emotional. And a few weeks later, his departure was even more emotional. Roman had not seen his mother or his older sister for 23 years. He had never met his young nephew or an array of other young relatives. He tried to convince his family to leave Poland and promised to help them through the formidable United States immigration process. He did not succeed. He knew that his mother was nearing the end of her life. And he sensed that he might never see some of his Łódź family members again.

The photographs taken during the first days of his Łódź stay show a smiling Roman. In the last photographs, taken in the courtyard of his mother's apartment building just before his departure, the smile had disappeared from his face. He left Poland in late February 1938, and traveled back through Germany and France to England just two weeks before the Anschluss and Hitler's takeover of Austria.

THE WAR YEARS AND BEYOND

In mid-March 1938 Roman returned to California and to his work at Universal. At home he found it too painful to talk with his children about his visit to his family in Łódź — we were just six and seven years old in 1938 — just as he had found it too painful to talk about the loss of his brother Jack two years earlier.

At work he quickly regained his footing — at least on the surface — working on Universal film sets, at out of town locations, and within the portrait gallery. And he kept occupied and engaged by continuing to be open to new ideas and new projects.

The first of these projects was completed between his return and the outbreak of war and was released in 1939 on the eve of the German invasion of Poland. It was a book written by Universal publicist Ray Hoadley with Roman supplying ideas and dozens of photographs. The book, which was the first of five in which Roman had a hand, was called How They Make a Motion Picture. It followed the process of film making and explained the role of the various departments — script writing, sets, costuming, makeup, lighting, dubbing, editing, photography and the many other specialties required to complete a talking film.

The book was well received within the film industry. It also received some national notice — at least some of which remains visible on the Internet today in the archives of the The Saturday Review of Literature. It is described as “A detailed narrative of the workings of Hollywood, profusely illustrated. . . Undistinguished but thorough”. Regardless of that tepid review, the book has survived as an introduction to the techniques used in the first decade of sound movies. The book is still available from used book dealers and the full text of the book can be found in several formats on the Internet, but without the many photographs Roman contributed.

From 1938 until years after World War Two apprehension about family members in Eastern Europe was a constant in the lives of both my parents. Life during the war years took on an almost surreal bifurcated quality for Roman. On the one hand he had his work, children, extended family — almost normal everyday life. But hovering in the background were daily reminders — the evening news, with the family gathered around and quite literally watching the radio, and everything from benign and even cheerful campaigns to sell war bonds or collect scrap metal to more somber visits from young relatives passing through Los Angeles on their way to active duty in Europe or the Pacific.

For Roman work had the same strangely disjointed quality. Hollywood geared up with everything from blood drives to churning out the uniquely World War Two material for the men on the front lines. Studios produced a huge volume of photos usually associated with two terms, “pinup” and “cheesecake” — both terms meaning pictures of sexy looking, scantily clad young women. And Hollywood fine-tuned its film themes, producing a number of upbeat patriotic films, many of them featuring some of the same pretty young women who were photographed in pinup poses.

Roman did his part producing dozens of pinups that were printed by the thousands and sent to servicemen and war workers all over the world. And he wrote articles helping amateurs understand how to photograph pictures for loved ones far away from home, including how to take pinup pictures and how to pose for them.

At the same time, more and more close friends, and Roman’s own nephew, Henry Freulich, left their work at film studios to join the armed forces. Roman himself attempted to enlist — I remember his efforts to fatten up his slender frame and to sit in the sun to give his skin a healthy glow. But he was turned down — he was over 40, still underweight, and had a medical history of tuberculosis.

Roman remained in Los Angeles and did what he could. He helped his sister-in-law, Jack’s wife Helene, to bring her half-brother and his family in to the United States in 1942 after they fled Warsaw and made their was through the middle east and Japan to Mexico. He helped organize Red Cross blood drives on the Universal Studio lot and took photographs of celebrities giving blood that the Red Cross later used to encourage more blood donors.

But the worry was always there throughout the war years. And even after the war it remained. For the rest of Roman’s life, though he continued making inquiries and corresponding with aid organizations, there was no information about family members who might have survived or those who were lost.

Republic Pictures

In 1945 Roman left Universal to join Republic Pictures as head of the still photography and portrait department. The transitional years — his last few years at Universal and first at Republic — were a busy time. Roman’s work was honored at the Solon International d’Art Photographiqiue de Luxembourg and with four Academy Awards.

During his 13 years at Republic the western played the same role as the horror film had played at Universal — it was the company bread and butter. Thus photographs of John Wayne, Roy Roger, Dale Evans, “Wild Bill” Elliot, Gabby Hayes, Gene Autrey and the Sons of the Pioneers began to take a prominent place in Roman’s portfolio.

Republic emulated Universal in another way — occasionally Herbert Yates, the studio head, backed a film that broke away from the B grade movie mold and produced (or attempted to produce) a quality film. Yates called these films his “Premiere” productions and often brought in directors and actors who were not studio regulars. But by 1958 profits were so low that Yates informed stockholders that Republic Studios would no longer produce original films. The Studio continued, instead, as a site for the independent production of films and television series, with Republic Pictures continuing as a film distributor.

The 1960s, rather than fulfilling an often heard prophecy that television would be the death of the film industry— a prophecy that for a time was shared by Roman — turned into a boom time for independent filmmaking. Roman had past his 60th birthday when production stopped at Republic. But, to say the least, he was not ready to retire. He continued to work on a free lance basis — most often on productions for the same directors and the same actors he had covered at Republic and often in the same Republic Studio facilities. But now he was free to pick projects and people with whom he enjoyed working. He continued to do so, less frequently to be sure, until 1970, when he worked on the film Tora, Tora, Tora. Some of Roman’s work during his 13 years at Republic and his 12 years as a free lance photographer can be seen below.

The Last Decade

The 1960s were also years when Roman could once again follow his desire to explore new directions. It was a time when he could decline work when he wished and travel where and when he and Katia wished. And he could write — something that he had tried in the 1930s with two avant-garde scripts and, increasingly in the 1940s, as a contributor to professional journals and fan magazines.

In 1964, the second book which bore his name as an author was published by Herzl Press. Unlike How They Make a Motion Picture, published 25 years earlier, the book was entirely his — he contributed most of the photographs and all of the writing. The book was called Soldiers in Judea, subtitled Stories and Vignettes of the Jewish Legion. It included a short preface, written by Edwin Herbert Viscount Samuel, who served as the first British High Commissioner in Palestine after World War One. Samuel noted that the book was “a collection of vivid little pictures of the men who served in the Battalions, their difficulties, their comic moments and their military achievements . . . Mr. Freulich is not a polished writer; but he has an eye for detail, and looks at his fellow-legionnaires with sympathy and understanding. These very qualities have enabled him to produce an untarnished account of events as they actually were.” And it drew comments in two hand written letters from Israeli Premier David Ben Gurion, who had served with Roman in the Jewish Legion. In one, dated March 6, 1965, Ben Gurion notes “there are a few (unimportant) inaccuracies (on page 190)” but states “I enjoyed reading your book from beginning to end. Old, past days came back alive” In the second, after Roman asked him to clarify the inaccuracies, Ben Gurion wrote:

I am gladly correcting the story on pages 189-190.

When the Zionist commission arrived in Palestine I was often called to it, especially by Dr. Weizmann. My Captain in order to facilitate my visits transferred me from my platoon to his office. Once I was invited by Weizmann and left immediately for Tel Aviv without asking permission to leave. The conversations continued the following day and [I] asked Weitzmann to ask Margolin to prolong my leave for another few days, which was immediately done. When I returned to camp I was arrested for being absent without leave. I lost my two stripes and was confined to barracks seven days. The whole story about Margolin (in this case), and my being unshaved, sulky — is pure invention. My relations with Col. Margolin were excellent.”

Four years later, in 1968, The Hill of Life, a fictionalized biography of Joseph Trumpeldor was published by Thomas Yoseloff. Trumpledor was one of the men who was instrumental in convincing the British to form the Jewish Legion during World War one and served as second in command of the Zion Mule Corps, the auxiliary unit that served during the World War One Gallipoli campaign. Trumpledor was killed defending Tel Chai settlement from an Arab attack in March, 1920.

Both Soldiers In Judea and The Hill of Life (much to my amazement) can still be purchased — used — online.

Retirement had proven to be a busy time for Roman. And the two books, both centered on World War One and the Jewish Legion, were followed by a trip to the Middle East — his first trip to the State of Israel, and the first time he had returned to the area since World War One.

Israel 1968 – And Beyond

In the spring of 1968, a celebration was held at Avichail, in Northern Israel. The celebration, like Roman’s two books, centered around the Jewish Legion.

Avichail is a moshav, an agricultural settlement near Netanyah, that was formed by members of the Jewish Legion who had remained in Palestine following the end of World War One. The celebration was for the opening of Beit Hagdudim, a museum of the Jewish Legion. The museum still serves as a repository for information and artifacts about the Legion.

Roman and Katia attended the celebration, along with former Legionnaires from around the world and along with David Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel, Yitzak Ben- Zvi, the first President of Israel, and Moshe Dayan, who in 1968 was serving as Israel’s Minister of Defense and who later served as Prime Minister. Ben Gurion and Ben Zvi had both served in the Jewish Legion.

Roman had turned 70 years old a few months before his trip to Israel. But he had not slowed down. And the trip provided him with an opportunity to produce a set of photographs that illustrate his expertise in capturing images on the fly. The only camera he carried with him was a small 35mm camera which freed him to shoot multiple pictures quickly without reloading. But he was remarkably spare in his use of the camera and almost all of his photographers were one of a kind. His "one shot" reputation seems to have served him well. The photographs from his trip are extraordinary.

In 1972, four years after Roman and Katia's trip to Israel, a book called Faces of Israel was released featuring about 200 of Roman's photographs. All of the original negatives and most of the original prints from the book are currently housed in the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles. A few of these photos can be viewed below. (In 2017, in honor of the 100th anniversary of the formation of the Jewish Legion we moved several other photos from Roman's 1968 trip, and added some additional photographs not previously used on our website, to a separate post called Israel - 1968.)

In 1971, a year before the publication of Faces of Israel, A.S. Barnes had published a book featuring Roman's photographs. The book was titled Forty Years in Hollywood: Portraits of a Golden Age. It featured photographs from Roman’s career — beginning with a his 1928 portrait of Conrad Veidt from the Universal Studio production of The Man who Laughs through his work at Republic studios and beyond. Roman was able to identify photographs for Forty Years in Hollywood and he narrated most of the anecdotes that appear in the book. But his health was declining and he was unable to put his stories on paper. His one request was that the stories, though most had to do with his own life in the film industry, be told in the third person.

Both Faces of Israel and Forty Years in Hollywood were well received and Faces of Israel became a featured selection of the Commentary Magazine Jewish Book Club.

Roman’s health continued to deteriorate and on his birthday, March 1, 1974, he died at the age of 76 — peacefully, at home in Beverly Hills, half a world away from his birthplace in Częstochowa. He was survived by Katia, his wife of almost 50 years.

During his last years Roman had become increasingly impatient with his photographic collection and increasingly anxious to simply discard it or burn it. Katia Freulich made it her business over these same years to preserve as much as she could of Roman's collection. Without her efforts, and her memory, much of this story would remain unknown to Roman's children, grandchildren and great grandchildren. And it would remain untold for the rest of our extended family.