The Obermans - America

After our Israeli and Australian cousins told us that Leo Oberman had survived the Holocaust we searched the available online genealogy site and quickly found the ship manifest pictured above.

After the Holocaust, Hersz Leyb Oberman married and immigrated to the United States. Leo and his wife, Toska Oberman, nee Klein, were sponsored by H.I.A.S. — the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society — and arrived in the Port of New York in June, 1948. Both were designated as “stateless.”

Additional records followed, though slowly. Everything we found in the United States indicated Leo and Toska settled in New York, began a new life, successfully supported themselves, started a family, and became naturalized citizens. Over the years they had two children, several grandchildren and several great grandchildren.

Discrepancies

Finding the ship manifest had been effortless.

Surprisingly, in all the immigration records we could find, the Leo Oberman aboard the Queen Mary in 1948 was the only immigrant of that name who came to the United States during at least the first three decades following World War Two. But there were obvious problems. And in the American records we began to accumulate the problems persisted.

We were looking for Leo Oberman, born in Częstochowa on April 2, 1904. But descendants of Leo and Toska we contacted consistently pointed out that their ancestor, Leo Oberman, who had arrived aboard the Queen Mary in the spring of 1948, was 32 years old when he arrived and had been born in Leipzig in 1914.

As records accumulated, again and again we found that the Leo Oberman who had arrived in 1948 stated that he was born on April 2, 1912 in Leipzig, Germany.

How could this Leo Oberman - born eight years after Hersz Leyb Oberman was born in Częstochowa— be our cousin?

A Gap in Time

Three years were missing from our records.

In our initial search we had found no records that covered the time period between the liberation of Dora Mittelbau slave laborers in April 1945 and the departure of the Queen Mary from Southhampton, England in June, 1948.

Perhaps, if we could find records of those three years, we would solve the mystery of Leo Oberman’s relationship to your Halborn family.

In an effort to fill in the gap we sent an enquiry to the International Tracing Service, the home of the Aronson Archives, which had not yet digitized its voluminous records or made them available online. We sent our request on August 8, 2018.

The ITS, at that time, investigated and answered all enquires in the order in which they were received and the agency was, surprisingly so many years after the Holocaust, still inundated with requests for information.

A full year passed before we received a reply.

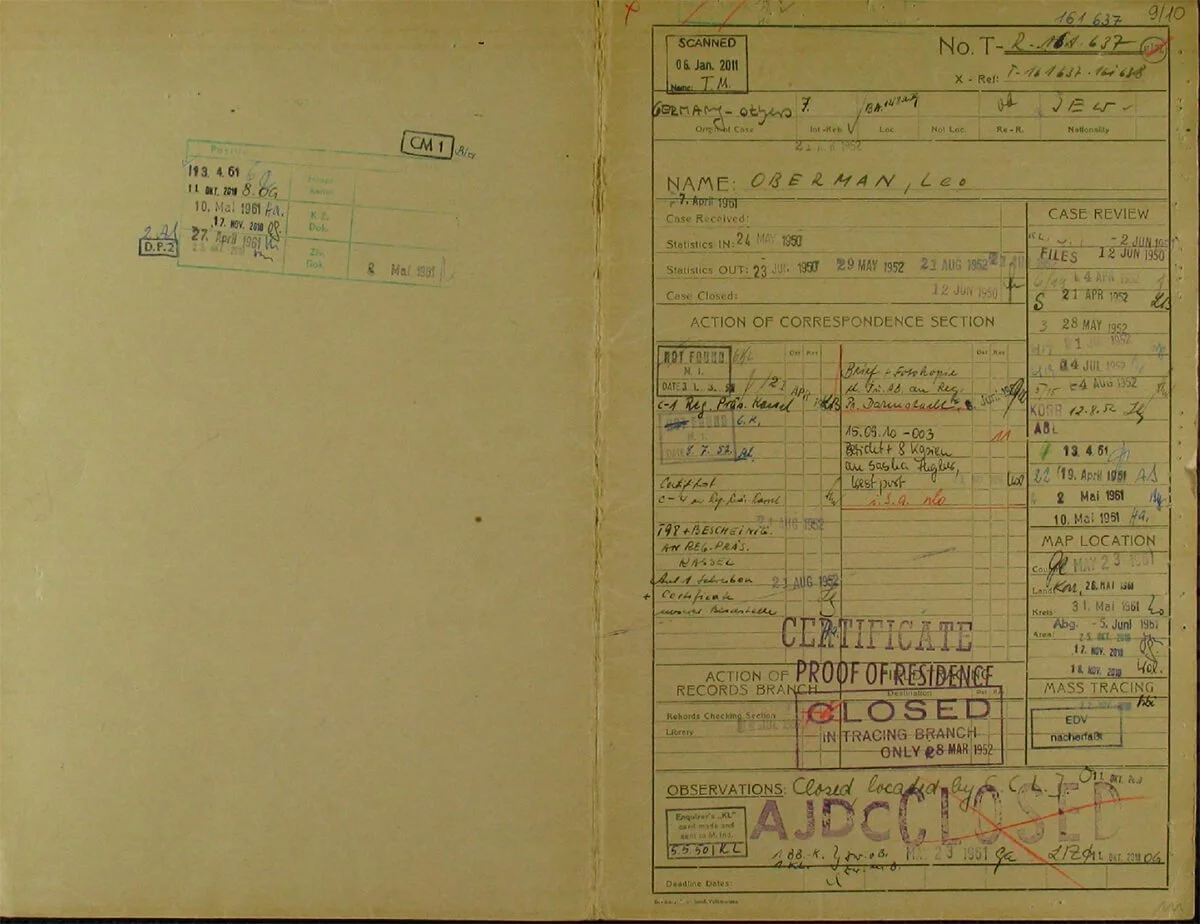

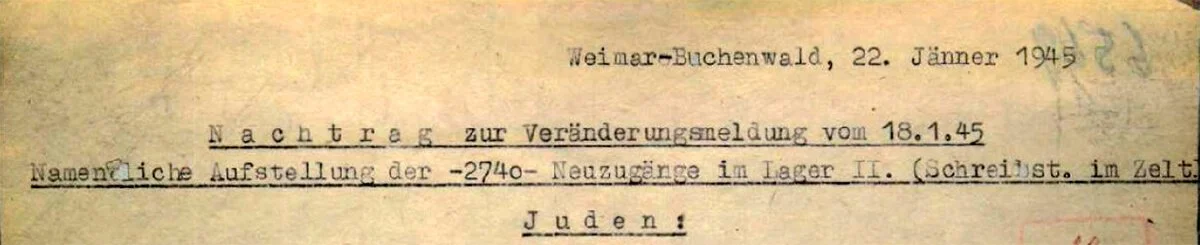

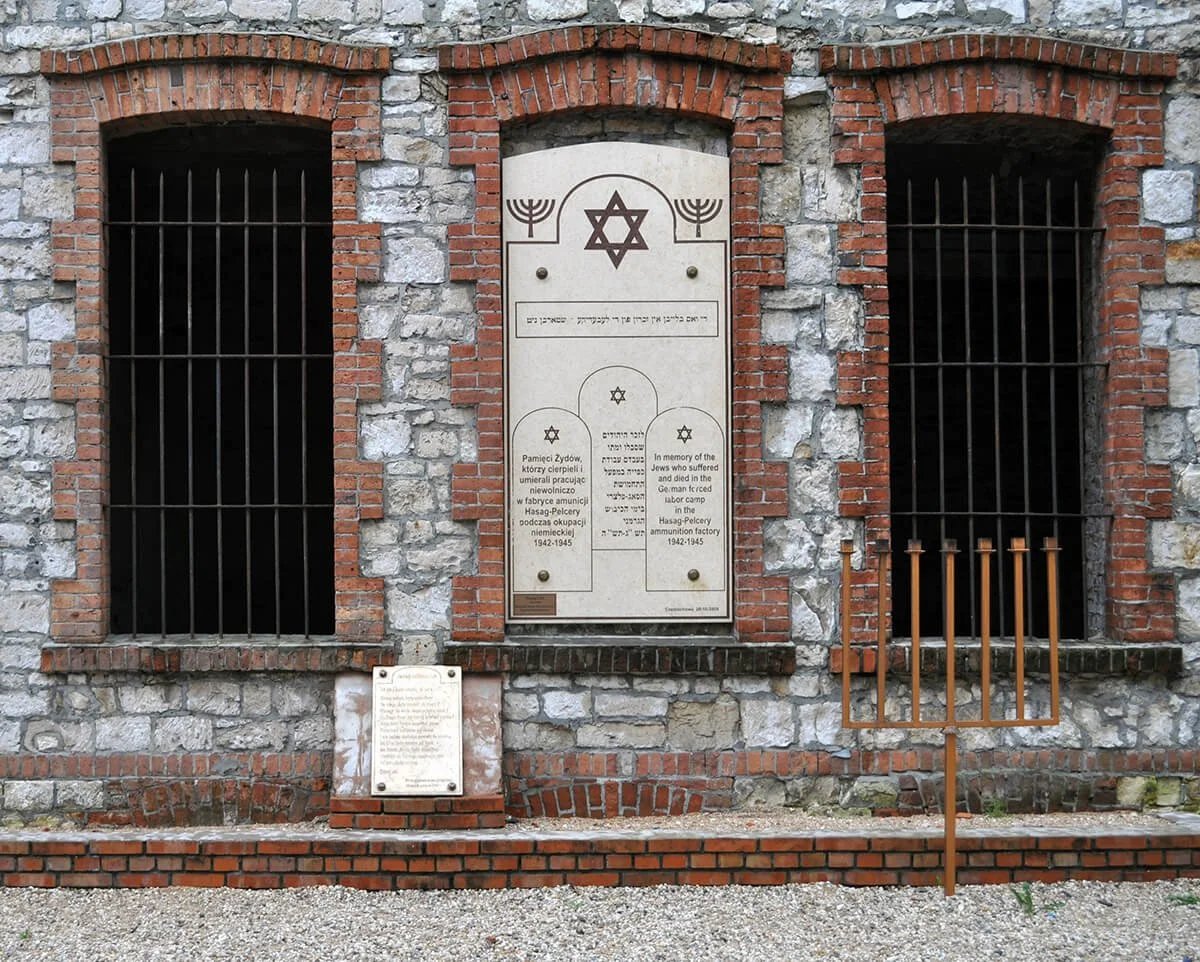

Then, on August 7, 2019, an email arrived from the International Tracing Service with an attached PDF file containing dozens of documents covering Leo Oberman’s time between his transfer in January 1945 from the Hasag-Pelcery slave labor camp in Częstochowa to Buchenwald and beyond.

In part, the documents solved our problem — we were able to fill in some of what happened in the missing three years after the war. But the documents also added to the puzzle: The Leo Oberman who arrived in New York aboard the Queen Mary on June 22, 1948 was definitely our cousin. But that same Leo Oberman still claimed, according to the documents, that he was born in Leipzig in 1912.

Here is what those records confirmed:

Bad Wildungen

By April, 1945, with American troops nearing the Harz Mountains, the SS moved the remaining Dora-Mittelbau workers considered well enough to work onto cattle cars and sent them on to Sachsenhausen and Ravensbrück. Only the dead and dying were left behind.

We know that Leo’s brother, Mojzesz Oberman, was not among those who were sent on. He perished in Dora-Mittelbau on March 8, 1945, just weeks before American troops reached the site.

Whether Leo was sent on to Ravensbrück or Sachsenhausen or was liberated in Dora Mittelbau is not clear. But he was one of the few who survived. And several months after American troops arrived, he made his way to a displaced persons camp at Bad Wildungen.

For almost two years, the DP camp served as his home.

Marriage

In Bad Windungen Leo Oberman met and married Toska Klein. Toska had arrived at the displaced persons camp in October, 1945, a few months after Leo. Her date of birth is listed in camp records as November 4, 1919 and her place of birth is listed, strangely, as Auschwitz.

Marriages between survivors who met at displaced persons camps were frequent and life affirming events. But they were not always free from complications. The marriage of Helena Oberman, wife of Leo's brother Mojzesz, who died in Dora Mittelbau just days before American troops arrived, provides an example.

Leo’s sister-in-law, Helena Oberman, who was born Chaja Katz, had gone through Hasag Pelcery incarceration along with her husband and with Leo. She survived the war after being separated from Mojzesz at some point — possibly when the Częstochowa ghetto was closed and Mojzesz and Leo were transferred to the SS slave labor barracks at Hasag Pelcery.

Several years ago, before we found the voluminous records that existed for the Oberman brothers, we located a 1947 record for a marriage of Chaja Katz Oberman and a man named Eliasz Sztajni. That marriage puzzled us for some time, until Roman Weinfeld acquired and translated the court record of the decision in the 1947 court case in which Chaja Katz Oberman's establish Mojzesz's death:

Protocol

April, 10th, 1947

In a public session the Grodzki Court in Dąbrowa Górnicza on the request of Chaja Oberman residing in Częstochowa at 13 Kopernika Street, examined the case to declare the death of her husband Mojżesz Oberman.

Present: Judge K. Sokołowski

After recognizing the case there appears a witness Jakub Rudoler who is living in Dzierżoniów, and he asks to hear him directly today to speed up the proceeding and not to let his hearing by the Dzierżoniów Court.

The Judge decided to hear him today and accept the documents attached to the request.

The witness Jakub Rudoler, 41, Mosaic faith, trader, living in Dzierżoniów, 21 Limanowskiego street, …, informed of responsibility for false testimony, testifies:

During my stay in Sosnowiec on Środula district in the ghetto, several people were sheltered in the bunker to avoid being deported to Auschwitz, but they were discovered and shot dead on the spot. Between those shot and killed there was also Mojżesz Oberman, who was known to me from Dąbrowa Górnicza where he resided. After his shooting I took his corpse to the hospital as well as the corpses of others shot dead. This happened on August 1, 1943 before noon.

The judge closed the meeting and announced the decision, setting the date of death on August 1, 1943 at 24:00.

After finding the judicial order, we listed Mojzesz Oberman's death date in our family trees as August 1, 1943. Only later, when the vast resources of the Arolsen Archives were made available on-line, did we find that Mojzesz had not perished in 1943, but died in Dora Mittelbau on March 3, 1945, just days before the arrival of American troops.

The irony is heart wrenching.

Leo Oberman was faced with a similar situation. He had acknowledged his marriage to Fela Szere in multiple records created during his short stay at Dora Mittelbau.

Unlike the situation of his sister-in-law, it appears that at Bad Wildungen Leo faced no requirement to prove that he was single. Whether this was because restrictions were only placed upon women, or simply because none of the records that later emerged with his wife's name were available at the time, is not clear. But he and Toska had no difficulty taking their marriage vows while both were residents of Bad Wildungen. Only years later, as more records surfaced and as inquiries continued to be made by relatives seeking to find either Toska or Leo, did the fact that Leo had married Fela Shere before the war become an issue. And it was probably an issue only on paper, as the International Tracing Service attempted to satisfy the inquiries that continued to pore in from family seeking to find either Toska Klein or Leo Oberman.

Angst and Chaos

The chronology of Leo Oberman’s stay in the Bad Wildungen Displaced Persons Camp, and of almost all the people listed on the page above, reflects the chaos and confusion that accompanied the months immediately following the war.

It is hard to remember (if one is old enough) and harder yet to imagine (if one is not old enough) what it was like to try to reconnect with family and friends after the horror of the Holocaust.

More victims were murdered than alive. Records maintained by Nazi functionaries were largely destroyed. And those records that remained were almost impossible to access and, even if available, were often inaccurate.

The infrastructure of most of Europe was largely destroyed. And even if pre-war services had been intact, they would have been overwhelmed and inadequate to the task of re-connecting families. Survivors and their relatives were dependent largely on written inquiries, radio messages or laborious travel — all unreliable and time consuming.

There was no way to rapidly ascertain the identity of those murdered or those who survived. And those who did survive were often fearful — traumatized, both physically and mentally to varying degrees — and often slow to trust their rescuers and to seek help finding any family and friends who were still among the living.

Nor should we forget that it took another half century for Internet access, which we take for granted, to become commonplace and even longer for any surviving Shoah records to be digitized and made available online.

I still recall my father and mother sending letter after letter to various agencies about my grandmother, aunts, and cousins, and waiting months for replies. Those replies, if they arrived at all, were almost always negative. My parents died decades after the Holocaust without knowing the fate of most of their loved ones who had remained in Europe. Only one aunt — an older sister of my mother — was eventually located (in the late 1950s) and brought to the United States.

To this day it is not clear whether Leo an Toska even knew about all of the enquiries being made about their survival or their whereabouts.

Searching For Family

When we sent our request for information about Leo Oberman to the International Tracing Service in 2018 we received an immediate reply informing us that the ITS was still swamped with more than 1,000 requests a month. They gave priority, they said, to survivors or people with urgent needs. Barring those special conditions, it would take a year or more to send us the information we requested.

The abundance of enquiries was, in no small part, due to the persistence of family members who, decades after the Holocaust, were still determined to find the fate of missing relatives. The results of early searches, conducted in the chaos of post-war Europe, without the accumulation of records that has occurred over the decades and without the assistance of today’s technology were often disappointing.

The search for Leo Oberman was no exception. And the persistent discrepancies in the records clearly made that search more difficult.

It is not surprising then, that the International Tracing Service required a full year to track down records we requested for Leo. When the ITS response arrived, the information was overwhelming. It included dozens of records of the time between the end of the war and the date Leo and Tosca Oberman traveled to the United States. And it continued on for several decades. And, because of the discrepancies, often involved exchanges between various government authorities, including police.

It is, then, not surprising that, once found, documents did not reveal the reasons for the multiple discrepancies that Leo had allowed to remain on the record.

The 1952 document above, is typical. A rough translation, in part, states that “the place of birth named by him, Leipzig, was not allowed to be used, as confirmation from the local authorities was not given.” It notes that Leo was probably single while imprisoned and gives, as the reason for this assumption the fact that he married Toska Klein in Bad Wildungen. It goes on to give the names of his parents. “Father: Chana Oberman, last living in Częstochowa. Mother: Rosa, born Heilborn.”

The record also asserts, based on available documents, that the only time Leo was in Częstochowa was between March 1940 through April 1941. And it concludes from this that he was in Buchenwald, Dora and Nordhausen from April, 1941 until the end of the war.

Clearly, this last assumption is not based on adequate evidence. We know both from pre-war records that Leo was born and lived in Częstochowa before the war. And we know from Hasag Pelcery records that the facility was evacuated in January 1945 as Russian troops moved through Poland. In addition, intake records (below), plus transport records (below) make clear Leo was one of many slave laborers sent to Buchenwald and then Dora Mittelbau in January, 1945.

The search for Toska Klein was less complicated. The letter below was typical: it was sent by Toska Klein’s uncle, Aron Hollander, in the spring of 1948. Hollander had apparently been looking for Toska for some time. Toska had probably lived in Cracow before the war and Hollander had obtained information from town authorities that she was living in a Berlin suburb a of Zollendorf, at Scheberstrasse 20.

The letter above, written in Polish, translated by Roman Weinfeld, reads:

To: The Tracing Office of Jewish Committee

Tłomackie Str.

I kindly ask [the Office] to search for my missing niece Tosia Klein living up to 1940 in Cracow, 30 Sławkowska str.. After contacting Cracow I was told she was registered by the Cracow Committee as having the address: Tosia Klein, Berlin, Zollendorf, Scheberstr 20. The letter I sent to that address returned. I kindly ask you to find her for me.

Aron Hollander

Wetzlar, 17 / 11 / 48 K - 4. IV. 1948

P.S. Tosia Klein is a daughter of Estera nee Hollander

Hollander’s request made its way a month later to the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in Munich, which sent the following note to Toska at the address he had provided:

When results did come back, they were often disappointing, or they arrived too late, as displaced persons moved on one step ahead of agencies charged with searching for them.

Despite the setback, investigators at the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in Germany continued the search and at the end of August, 1948, they received the following message:

The information, unfortunately, reached Toska’s uncle two months after Leo and Toska had left Europe for America. We do not know if Hollander was able to contact his niece or see her again.

But, according to the American Joint Distribution Committee, the couple did not leave for England until July 1947. According to the American Joint Distribution Committee records, they left Frankfurt for England on July 2, 1947.

Jon Acker, who is a descendant of Huna Oberman's half sister, Lina Oberman, had been central in helping us locate the descendants of Leo's older brother, Berek Oberman. He had also informed us that Leo Oberman had survived the war. And he had put us in touch with Leo's American descendants. Now, once again, he provided valuable information about Leo and Tosca's time in England.

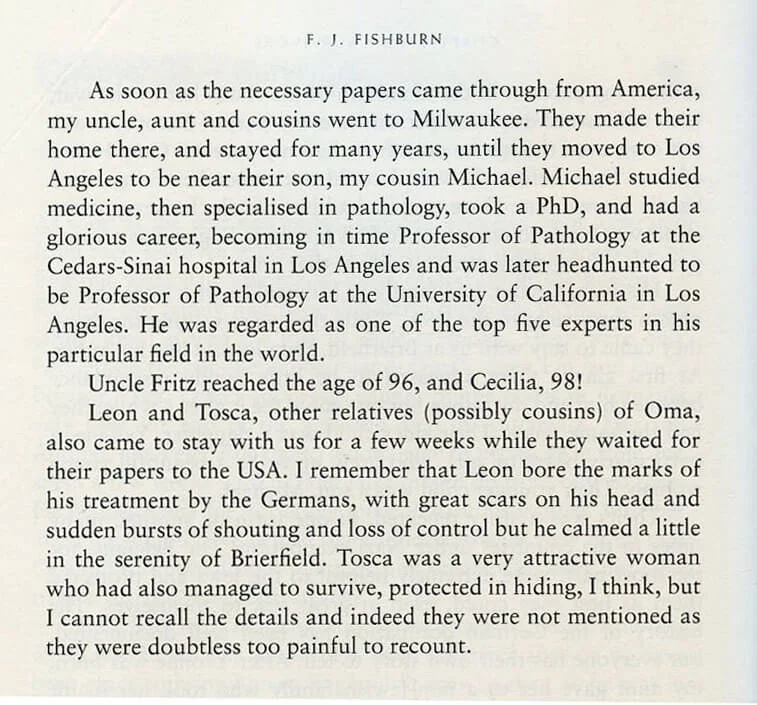

Jon told us that Jack Fischbein's son, Fred, was a young boy during Leo and Toska's stay and remembered that stay well: his family had persistently searched for several relatives who they hoped had survived the relatives and had housed them, leaving a permanent record of family generosity in his mind. Years later he wrote a book that covered that era of his family life.

Jon Acker also met with Fred Fishburn in early 2019 and provided the following information

Yesterday I met with Fred Fishburn, the grandson of Sura Oberman (Leon's cousin and Sister of my great-grandmother Lina).

He found this family photo with Leon and Tosca in which he marked out who's whom. He told me again that Leon was badly wounded to the head that this was clearly visible. I told him about the documents we found of him being at the forced labour camp, which he again said tallied with how Leon seemed to him (terrible nightmares etc) when this photo was taken (sometime in the late 40's), probably before Leon and Tosca left for the states. He said that Tosca was an exceptionally beautiful woman.

America

It was Leo Oberman’s Social Security death record that convinced us the man who had arrived in the United States in 1948 aboard the Queen Mary was the same man who had suffered years of slave labor in the Hasag Pelcery camp in Częstochowa — the same man who survived the final months of the war in early 1945 working in the Dora Mittelbau underground V2 rocket assembly plant.

The Aronsen Archives recode sent to us in 2019 substantiates our conviction.

It was impossible to ignore the most import factors shaping Leo’s response to the Holocaust: five years of slave labor and the agony of surviving Nazi rule that had murdered so many, including every member of his family who had remained in Poland when Nazi Germany invaded in September, 1939.

But Leo Oberman never forgot his father and ismother: Hua Oberman and Rywka Oberman, nee Halborn.

Leo was our cousin, Hersz Lejb Oberman.